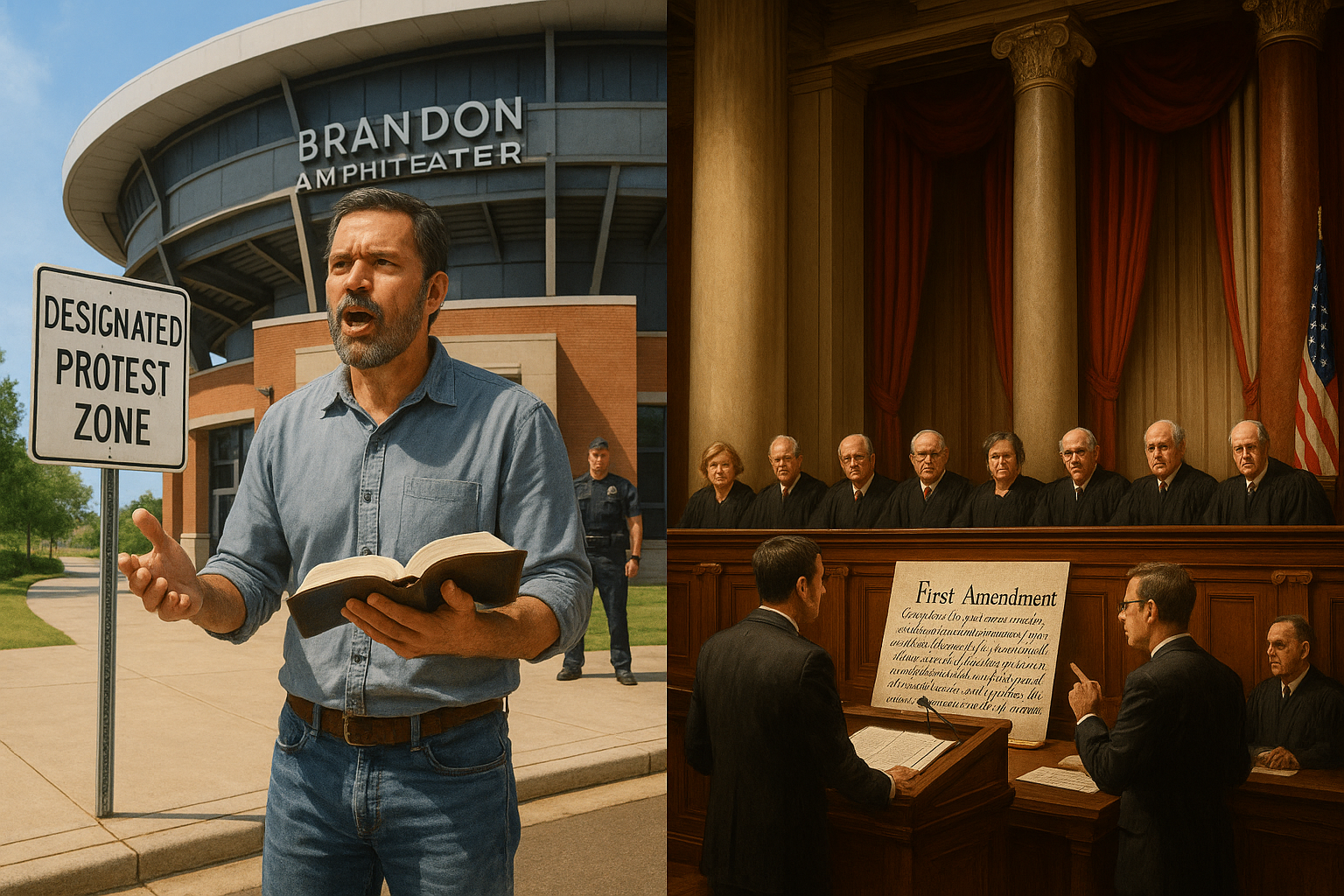

The U.S. Supreme Court on Wednesday heard arguments in a case brought by Mississippi street preacher Gabriel Olivier, who is asking to move forward with a federal civil-rights challenge to a Brandon, Mississippi ordinance that restricts where he may preach outside a city amphitheater. Olivier, convicted and fined in 2021 for violating the rule after preaching outside a designated protest area, says the law infringes his First Amendment rights and that he should be able to seek protection against future enforcement despite his past conviction.

Gabriel Olivier, an evangelical Christian street preacher from Mississippi, often travels to public spaces to share his faith. Court records and news reports say he began preaching outside the Brandon Amphitheater, a city-owned venue east of Jackson that can hold thousands of concertgoers, several times between 2018 and 2019.

In 2019, the City of Brandon adopted an ordinance governing demonstrations near the amphitheater. According to the city and federal court filings, the measure requires protesters to gather in a designated protest area during events and restricts the use of loudspeakers that can be heard more than 100 feet away. City officials said they acted after receiving complaints that Olivier and his group shouted insults and caused disturbances outside the venue, including yelling terms such as “Jezebel,” “nasty” and “drunkards” at people attending shows.

Olivier, represented by First Liberty Institute and allied attorneys, has said he views his street preaching both as a command of Scripture and as protected expression under the First Amendment. He contends the ordinance effectively pushes him away from his intended audience by forcing him into the protest zone, which the city has described in legal filings as roughly 265 feet from his preferred preaching spot near the main walkway.

In May 2021, after the ordinance was in effect, Olivier returned to his original location near the amphitheater instead of remaining in the designated zone. Police cited him for violating the ordinance. He later pleaded no contest in municipal court, received a fine and a suspended sentence, and did not serve jail time, according to court documents and multiple news accounts.

Rather than appeal his conviction through the state system, Olivier filed a federal civil-rights lawsuit under Section 1983. He sought damages and an injunction barring Brandon from enforcing the ordinance against him in the future, arguing that the law violates his freedoms of speech and religion and improperly isolates speakers from those they are trying to reach.

Lower federal courts dismissed his suit. Citing the Supreme Court’s 1994 decision in Heck v. Humphrey, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit held that Olivier could not pursue a Section 1983 claim that would undermine the validity of his still-standing conviction. The ruling left him, his lawyers say, in a legal “catch-22”: he was not jailed and thus could not seek habeas relief, yet his conviction blocked his civil suit.

The City of Brandon, represented by attorney G. Todd Butler, argues that the case is not fundamentally about religious expression but about the procedures available to people who have been convicted in criminal court. In public statements and legal briefs, the city has said that Olivier could have used state-law mechanisms or direct appeals to challenge his conviction and the ordinance but chose instead to mount what it calls a collateral attack through a civil lawsuit that also seeks monetary damages and attorney’s fees.

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court heard arguments on whether Olivier may press his Section 1983 challenge despite his prior conviction. News outlets that covered the proceeding reported that the justices focused on how far the Heck precedent should extend when a plaintiff seeks forward-looking relief rather than the outright invalidation of a conviction, and whether rigid application of that rule could improperly close the courthouse doors to some civil-rights claims.

Olivier’s legal team argues that allowing his suit to proceed would protect the rights of speakers across the ideological spectrum. “The Court should confirm that the federal courthouse doors remain open to persons like Olivier whose rights have already been infringed,” attorney Allyson Ho told reporters after the hearing, according to several broadcast reports. First Liberty lawyers have likewise maintained in interviews that the ordinance, by confining speakers to a distant protest zone, makes it difficult to hold conversations, hand out literature or be heard by passersby.

City officials and their supporters counter that the ordinance is a neutral time, place and manner regulation intended to manage large crowds and public safety near the amphitheater, not to target religious viewpoints. They say the rule applies to all demonstrations during set hours around events and note that the designated protest area still allows Olivier and others to speak, carry signs and express their views.

Olivier has disputed characterizations that he engaged in unlawful disorderly conduct, pointing to existing laws that already address genuinely disruptive behavior. He has said in interviews that his aim is not to relitigate his past municipal case but to secure clarity and protection for his ability to continue preaching near the amphitheater and in similar public forums.

The court’s eventual ruling, expected later in the term, is likely to shape how lower courts apply Heck v. Humphrey to civil-rights lawsuits that follow minor criminal convictions and could affect how people across the country challenge local ordinances in federal court while still seeking to speak in public spaces.