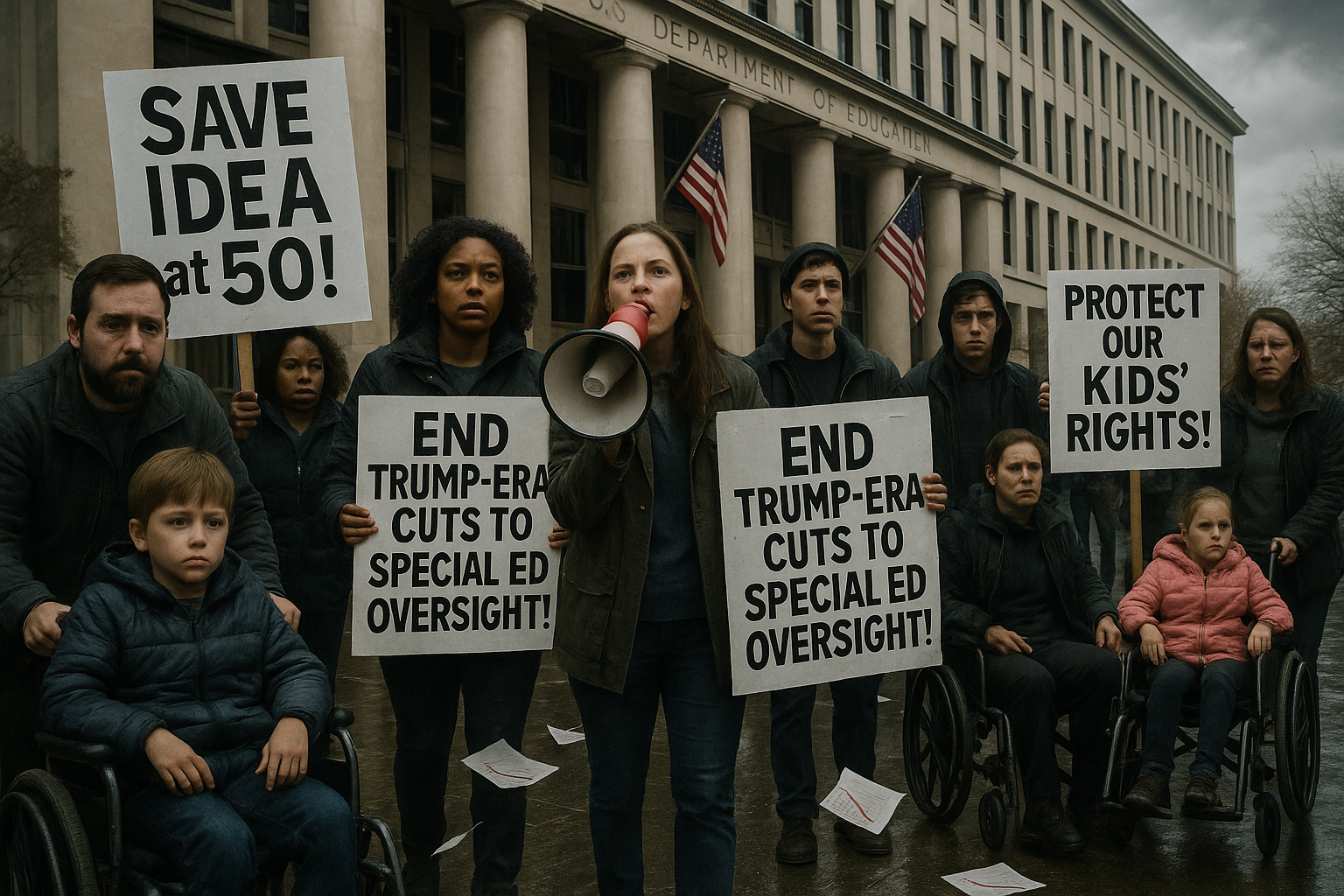

As the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) approaches its 50th anniversary, disability rights advocates warn of a crisis in federal oversight, citing Trump-era staff reductions and policy shifts at the U.S. Department of Education’s civil rights and special education offices. They worry that weakened enforcement could erode protections that ended the widespread exclusion of children with disabilities from public schools.

In 1975, just after Thanksgiving, President Gerald Ford signed the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, later renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA. The law guarantees eligible children with disabilities a “free appropriate public education” in the least restrictive environment. Before the statute was enacted, researchers and federal officials estimated that only about one in five children with disabilities attended public schools, and that roughly 1.8 million such children were excluded entirely from public education.

Ed Martin, one of the law’s early advocates, has described these children as often being kept at home or in institutions and rendered “invisible” to the public school system.

Under former President Donald Trump, the U.S. Department of Education pursued staffing cuts and policy changes that advocates say weakened enforcement of disability rights in schools, according to reporting by NPR. The Office for Civil Rights (OCR), which investigates complaints of discrimination on the basis of disability and other protected characteristics, reduced staff and moved to streamline its case-processing rules, raising concerns among advocates that fewer systemic investigations would be opened.

The article also notes that the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services (OSERS), which oversees IDEA implementation, experienced leadership turnover and internal restructuring during the Trump administration. Advocacy groups argue these shifts, combined with budget and staffing pressures, signaled a diminished federal role in monitoring how states and districts serve students with disabilities. Precise, nationwide counts of employees dismissed or reassigned at OSERS and OCR during this period, however, are not publicly documented at the level of detail sometimes claimed by critics.

Education policy officials aligned with Trump have argued that returning more control over education to states does not mean ending federal support for special education, but rather limiting what they call Washington “micromanagement.” In public statements and opinion pieces, they have said federal dollars for services under IDEA would continue to flow to states and local districts, even as the Department sought to shrink or reorganize certain offices.

Federal budget documents show that IDEA Part B grants to states have totaled more than $13 billion annually in recent years, helping fund services for millions of children with disabilities in kindergarten through 12th grade. Advocates, including leaders of the Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates, counter that money alone is not sufficient if there are too few federal staff to investigate complaints or enforce compliance when districts fall short.

Parents around the country have reported difficulties getting timely responses to complaints about the treatment of their children with disabilities in school. An NPR investigation documented cases in which families alleged that children were improperly restrained or secluded and said that subsequent OCR investigations moved slowly or were closed without broader remedies.

In one such case described by NPR, a family in a Kansas City–area suburb said their teenage daughter with Down syndrome was secluded in a small, padded room at school after she resisted a classroom activity. The child’s mother said the incident prompted her to withdraw her daughter from the school and that her daughter’s health and behavior deteriorated afterward. The family filed a complaint with the Office for Civil Rights, but the mother told NPR that the investigation dragged on amid staff changes at the agency.

Former Education Secretary Margaret Spellings has emphasized that IDEA has long enjoyed bipartisan support and that it is meant not only to provide services but to help students with disabilities become “productive citizens.” Disability rights organizations say this history makes recent federal retrenchment particularly troubling.

Publicly available data show that OCR’s overall civil rights enforcement activity fluctuated during the Trump years, and disability rights groups contend that the agency placed greater emphasis on resolving complaints quickly than on opening broad, systemic investigations. NPR’s reporting found that, compared with prior years, fewer large-scale disability discrimination cases against school districts were launched or fully investigated during Trump’s term, even as parents and advocates continued to file thousands of complaints.

Advocates warn that if federal oversight continues to shrink or be deprioritized, the burden will fall increasingly on families and under-resourced state agencies to enforce students’ rights under IDEA — raising fears that, over time, some schools could edge back toward practices that once kept many children with disabilities out of public classrooms.