Researchers at the University of Tokyo have built a bidirectional, label-free microscope that captures micro- and nanoscale activity in living cells without dyes. Nicknamed the “Great Unified Microscope,” the system combines forward- and back-scattered light detection to broaden what scientists can see inside cells, including changes during cell death and estimates of particle size and refractive index.

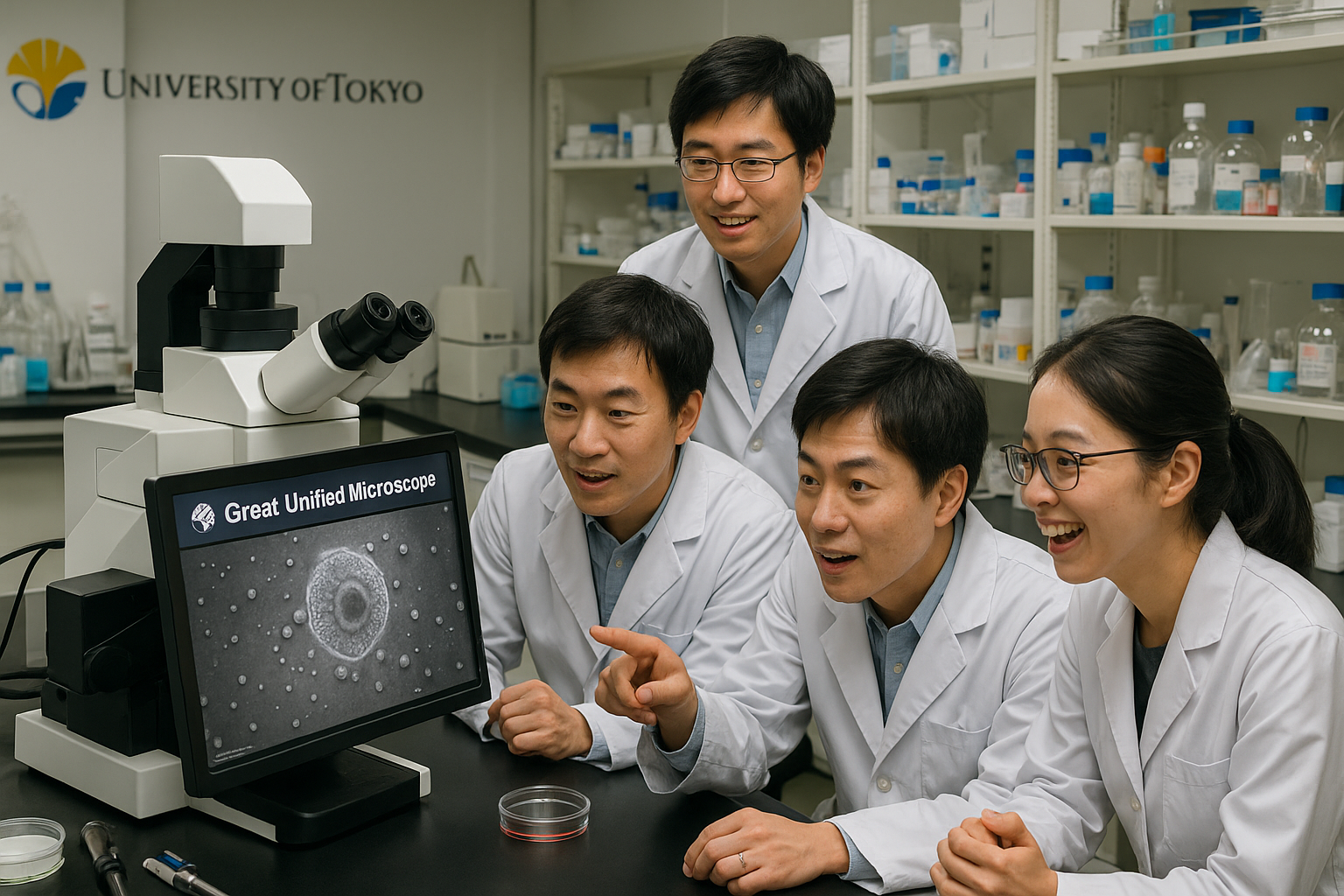

The University of Tokyo has unveiled a microscope that records both forward- and backward‑scattered light from living cells at the same time, allowing researchers to visualize large cellular structures and fast‑moving nanoscale particles in a single view. In their peer‑reviewed paper, the authors call the approach bidirectional quantitative scattering microscopy (BiQSM). The nickname “Great Unified Microscope” appears in the university’s press materials and related coverage.

How it works

- Conventional quantitative phase microscopy (QPM) measures forward‑scattered light and is well suited to visualizing microscale structures—defined in this study as features over roughly 100 nanometers—but struggles with very small, rapidly moving objects.

- Interferometric scattering (iSCAT) microscopy measures back‑scattered light and can detect nanoscale targets, including single proteins, yet lacks the broader contextual view QPM provides.

- By capturing light from both directions simultaneously, the new system bridges those capabilities. In Nature Communications (published November 14, 2025), the team reports a dynamic range 14 times wider than QPM in their experiments, enabling simultaneous imaging of nanoscale dynamics and microscale structure—without fluorescent labels.

What the researchers did and found

- The instrument was developed by Kohki Horie, Keiichiro Toda, Takuma Nakamura and Takuro Ideguchi, all at the University of Tokyo. Horie and Toda are co‑first authors.

- To validate the setup, the group monitored cells as they progressed toward death, recording image data that contained both forward‑ and backward‑scattering signals in one frame. “I would like to understand dynamic processes inside living cells using non‑invasive methods,” said Horie. “Our biggest challenge,” added Toda, “was cleanly separating two kinds of signals from a single image while keeping noise low and avoiding mixing between them,” according to the University of Tokyo’s press release.

- By comparing patterns in the forward and back‑scattered signals, the team could track the motion of larger cellular structures alongside much smaller particles and, according to the university, estimate each particle’s size and refractive index.

Why it matters

- Because the technique is label‑free and gentle on cells, it could be useful for long‑term observations and for applications such as testing and quality control in pharmaceutical and biotechnology settings, the university notes.

What’s next

- “We plan to study even smaller particles, such as exosomes and viruses, and to estimate their size and refractive index in different samples,” Toda said. The authors also aim to better describe how cells advance toward death by controlling cellular states and cross‑checking their results with other methods.

Publication details

- The study, “Bidirectional quantitative scattering microscopy,” was published in Nature Communications on November 14, 2025, by Horie, Toda, Nakamura and Ideguchi of the University of Tokyo.