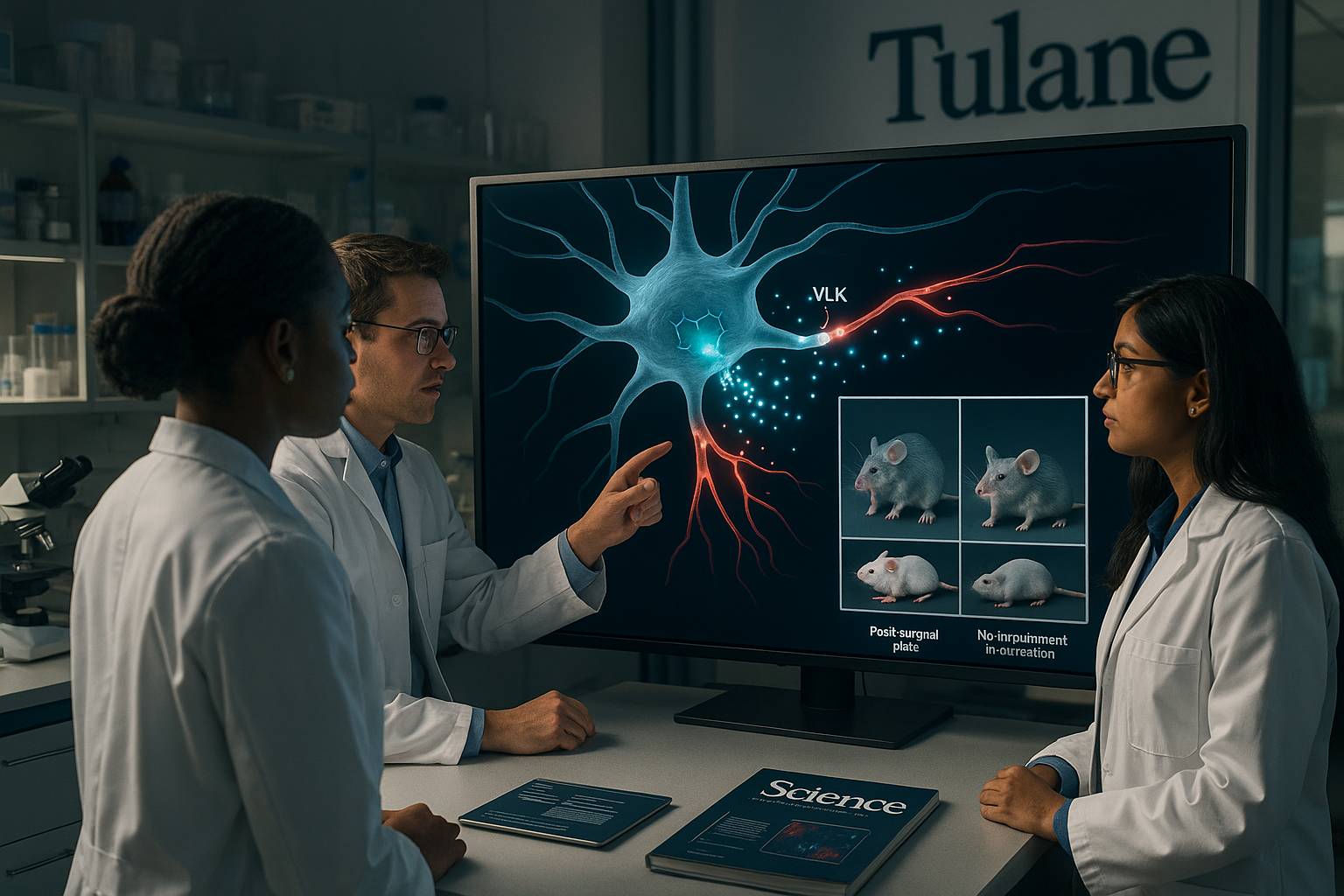

Scientists at Tulane University and collaborating institutions have found that neurons release an enzyme called vertebrate lonesome kinase (VLK) outside cells to help switch on pain signals after injury. Removing VLK from pain-sensing neurons in mice sharply reduced post-surgical pain–like responses without impairing normal movement or basic sensation, according to a study in Science, suggesting a potential new route to more targeted pain treatments.

Researchers led by Matthew Dalva at Tulane University's Brain Institute, in collaboration with Ted Price at the University of Texas at Dallas and teams from eight other institutions, have identified a previously unrecognized way that nerve cells communicate.

Their work shows that neurons release an enzyme known as vertebrate lonesome kinase (VLK) into the extracellular space, where it modifies proteins on nearby cells and intensifies pain signaling following injury. The same signaling pathway also helps strengthen synaptic connections involved in learning and memory, according to Tulane and University of Texas at Dallas releases.

"This finding changes our fundamental understanding of how neurons communicate," Dalva said. "We've discovered that an enzyme released by neurons can modify proteins on the outside of other cells to turn on pain signaling — without affecting normal movement or sensation."

The team found that active neurons release VLK, which boosts the function of a receptor system involved in pain, learning and memory that includes the NMDA receptor pathway. In mouse experiments, removing VLK from pain-sensing neurons greatly reduced typical injury- and post-surgical–type pain hypersensitivity while leaving movement and basic sensory abilities intact. When VLK levels were increased, pain responses intensified.

"This is one of the first demonstrations that phosphorylation can control how cells interact in the extracellular space," Dalva said. "It opens up an entirely new way of thinking about how to influence cell behavior and potentially a simpler way to design drugs that act from the outside rather than having to penetrate the cell."

Ted Price, director of the Center for Advanced Pain Studies and professor of neuroscience at the University of Texas at Dallas, underscored the broader implications. "This study gets to the core of how synaptic plasticity works — how connections between neurons evolve," he said. "It has very broad implications for neuroscience, especially in understanding how pain and learning share similar molecular mechanisms."

Because NMDA receptors are important for normal brain function and can cause side effects when broadly blocked, the researchers say in institutional statements that targeting VLK or related extracellular signaling molecules could offer a safer way to modulate pain pathways. By acting on enzymes that work outside cells, future drugs might be able to adjust pain signaling without having to enter neurons or shut down key receptors directly.

The study, published November 20, 2025, in the journal Science (volume 390, issue 6775; DOI: 10.1126/science.adp1007), involved collaborators at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, the University of Houston, Princeton University, the University of Wisconsin–Madison, New York University Grossman School of Medicine and Thomas Jefferson University.

The research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Center for Research Resources, all part of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Ongoing work is aimed at determining whether this extracellular phosphorylation mechanism affects a limited set of proteins or represents a broader biological process with implications for other neurological and systemic diseases.