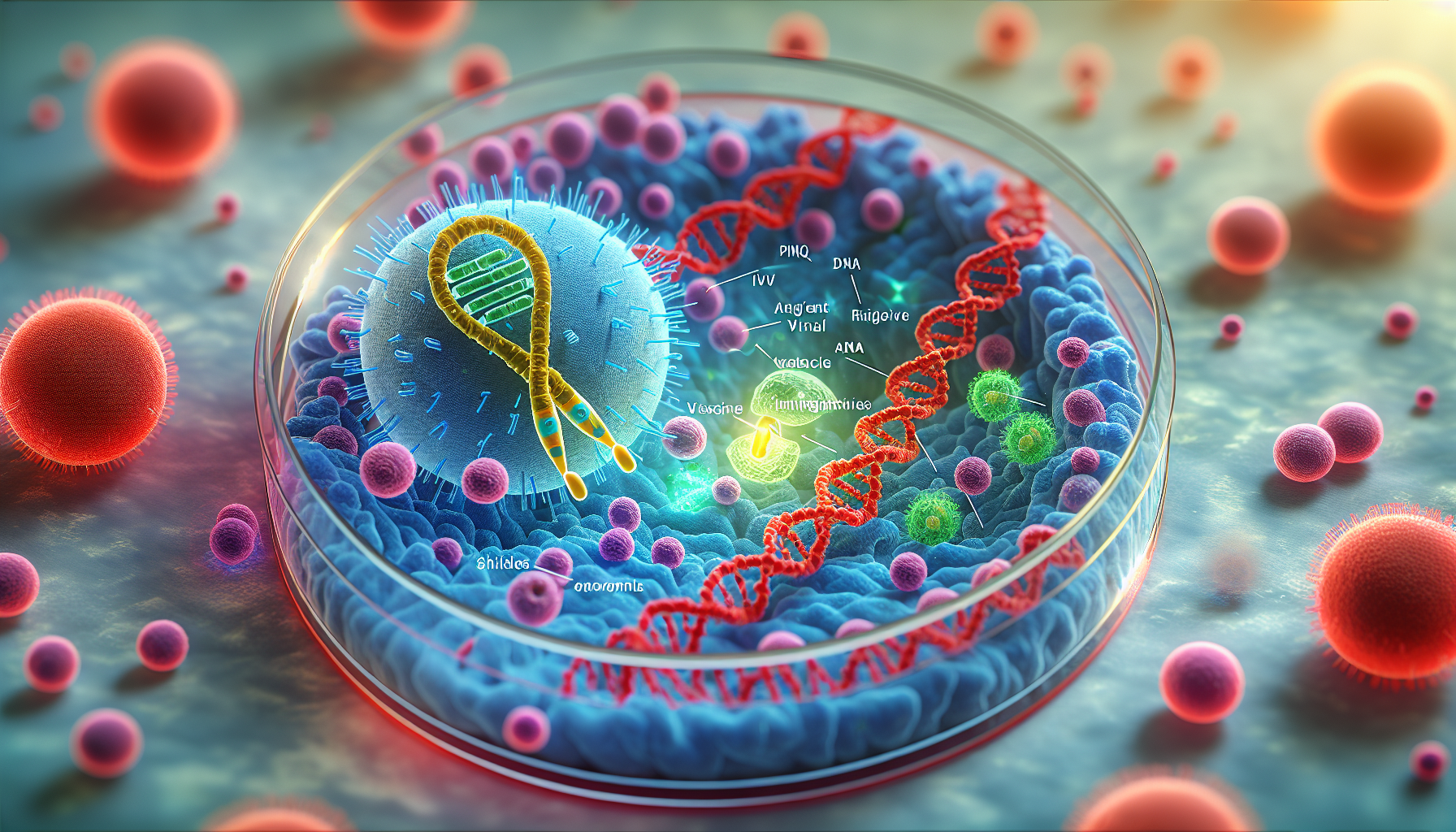

Penn State researchers report a bacterial defense that repurposes dormant viral DNA: a recombinase enzyme called PinQ flips a stretch of genome to produce protective proteins that block infection, work described in Nucleic Acids Research.

Scientists have long suspected that "fossil" viruses embedded in bacterial genomes can influence how microbes fend off new invaders. A Penn State-led team now details how one such system works and how it might inform future antivirals. (psu.edu)

- What the study found The team examined cryptic prophages—ancient, inactive viruses nestled in bacterial DNA—and identified a defense in Escherichia coli triggered by the enzyme PinQ. When phage attack looms, PinQ inverts a 1,797-base-pair segment in a separate cryptic prophage, generating chimeric proteins that block the T2 phage from attaching to the cell surface, the crucial first step of infection. The peer-reviewed paper identifies StfE2 as the primary inhibitor (with StfP2 contributing) and maps how these proteins interfere with T2’s adhesin, Gp38, at outer-membrane receptors OmpF and FadL. (academic.oup.com)

“Antibiotics are failing, and the most likely substitute is viruses themselves,” said Thomas K. Wood, professor of chemical engineering at Penn State, who led the research, adding that understanding bacterial anti-phage defenses is essential before therapeutic phages can be used widely. (psu.edu)

How they tested it

In lab assays, the researchers overproduced the inversion-derived proteins in E. coli and challenged the bacteria with T2. Turbidity measurements indicated reduced phage activity, and in directed-evolution experiments over eight passages, T2 escaped primarily by mutations in gp38, consistent with the adsorption-blocking mechanism. Computational modeling supported how StfE2 can disrupt Gp38 interactions with OmpF and FadL, aligning with experimental data. (psu.edu)Why it matters

Although recombinases have been noted near bacterial defense loci, the authors report this as the first demonstration that a recombinase directly activates anti-phage defense by inverting DNA to produce antiviral proteins. Beyond basic biology, the work could inform phage-based alternatives to some antibiotic uses and help optimize industrial fermentation processes such as yogurt and cheese. (psu.edu)Publication, authors, and support

The study, “Adsorption of phage T2 is inhibited due to inversion of cryptic prophage DNA by the serine recombinase PinQ,” was published in Nucleic Acids Research (Volume 53, Issue 19; DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkaf1041). Authors include Joy Kirigo; Daniel Huelgas‑Méndez; Rodolfo García‑Contreras; María Tomás; Michael J Benedik; and Thomas K. Wood. Funding came from the Biotechnology Endowment, the National Autonomous University of Mexico, and the Secretariat of Science, Humanities, Technology and Innovation. (academic.oup.com)What’s next

According to Penn State, the team plans to probe antiviral potential across eight additional prophages now under study in the lab. (psu.edu)