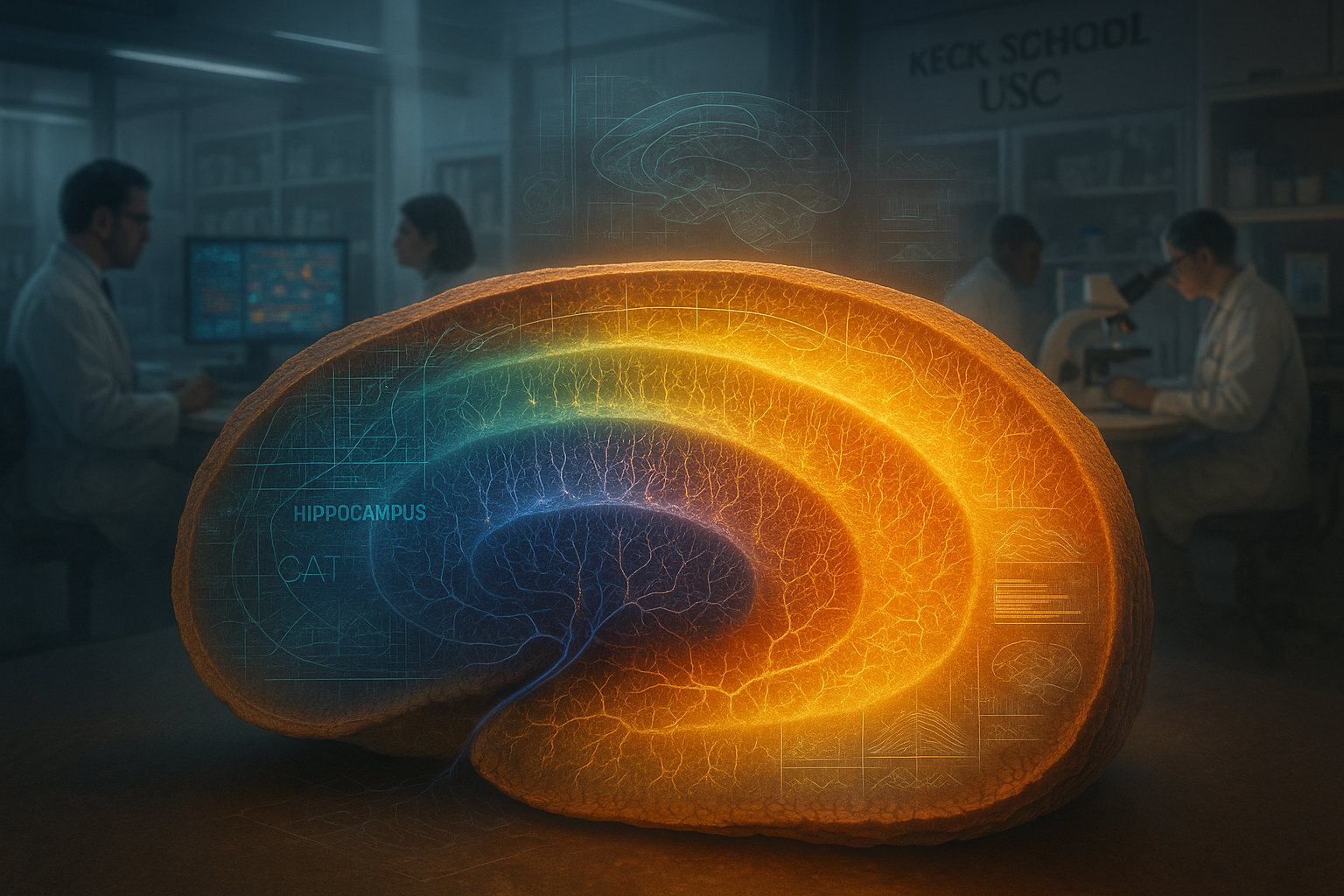

Scientists at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California have identified a four-layer organization of neuron types in the mouse hippocampus’s CA1 region, a key hub for memory, navigation, and emotion. The study, published in Nature Communications in December 2025, uses advanced RNA imaging to chart genetic activity in tens of thousands of neurons and reveals shifting bands of specialized cells that may help explain behavioral differences and disease vulnerabilities.

The hippocampus, crucial for forming memories, spatial navigation, and aspects of emotional processing, has long been known to vary functionally across its subregions. A new study from the Mark and Mary Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute (Stevens INI) at USC’s Keck School of Medicine reports a previously unseen layered structure within the CA1 subregion of the mouse hippocampus.

Published online in Nature Communications on December 3, 2025, the research describes four continuous bands of CA1 pyramidal neurons, each distinguished by a specific pattern of gene expression. The work builds on the team’s earlier Hippocampus Gene Expression Atlas, which had suggested that CA1 might harbor hidden sublayers of cell types.

Using an RNA labeling technique called RNAscope combined with high‑resolution fluorescence microscopy, the researchers labeled four marker genes and examined mouse CA1 tissue at single‑molecule resolution. According to the study, they quantified approximately 332,938 RNA transcripts within 58,065 pyramidal layer cells, creating a detailed cellular atlas that outlines boundaries between distinct neuron types across the entire CA1 axis.

Their analysis showed that CA1 neurons are arranged in four thin, continuous sheets that extend along the rostrocaudal length of the hippocampus. These sheets form laminar layers that differ in thickness and position depending on the CA1 subregion, rather than forming a uniform mixture of cell types.

“Our study shows that CA1 neurons are organized into four thin, continuous bands, each representing a different neuron type defined by a unique molecular signature. These layers aren’t fixed in place; instead, they subtly shift and change in thickness along the length of the hippocampus,” said senior author Michael S. Bienkowski, PhD, an assistant professor of physiology and neuroscience and of biomedical engineering at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

Co‑first author Maricarmen Pachicano, a doctoral researcher at the Stevens INI’s Center for Integrative Connectomics, highlighted the visual clarity of the data: “When we visualized gene RNA patterns at single‑cell resolution, we could see clear stripes, like geological layers in rock, each representing a distinct neuron type.”

The authors report that this layered organization offers a new framework for understanding why different parts of CA1 support different behaviors, including memory, navigation, and emotion, and why some neuron types appear more vulnerable in disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and epilepsy, in which the hippocampus is often affected early. Prior work has shown that the hippocampus is among the first regions impacted in Alzheimer’s disease and is also implicated in epilepsy and other neurological conditions.

The team integrated their results into an updated CA1 cell‑type atlas using data from the Hippocampus Gene Expression Atlas. According to materials from the Keck School of Medicine of USC, this resource is publicly available and includes interactive 3D visualizations that can be explored via the Schol‑AR augmented‑reality app developed at the Stevens INI.

Comparisons with existing anatomical and gene‑expression data suggest that similar laminar arrangements may be present in primate and human hippocampus, including comparable variation in CA1 thickness, though the authors note that additional work will be needed to define how closely human patterns match those observed in mice.

The study, which cites support from U.S. federal research funding agencies including the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation, was led by Bienkowski and Pachicano, with additional authors including Shrey Mehta, Angela Hurtado, Tyler Ard, Jim Stanis, and Bayla Breningstall.