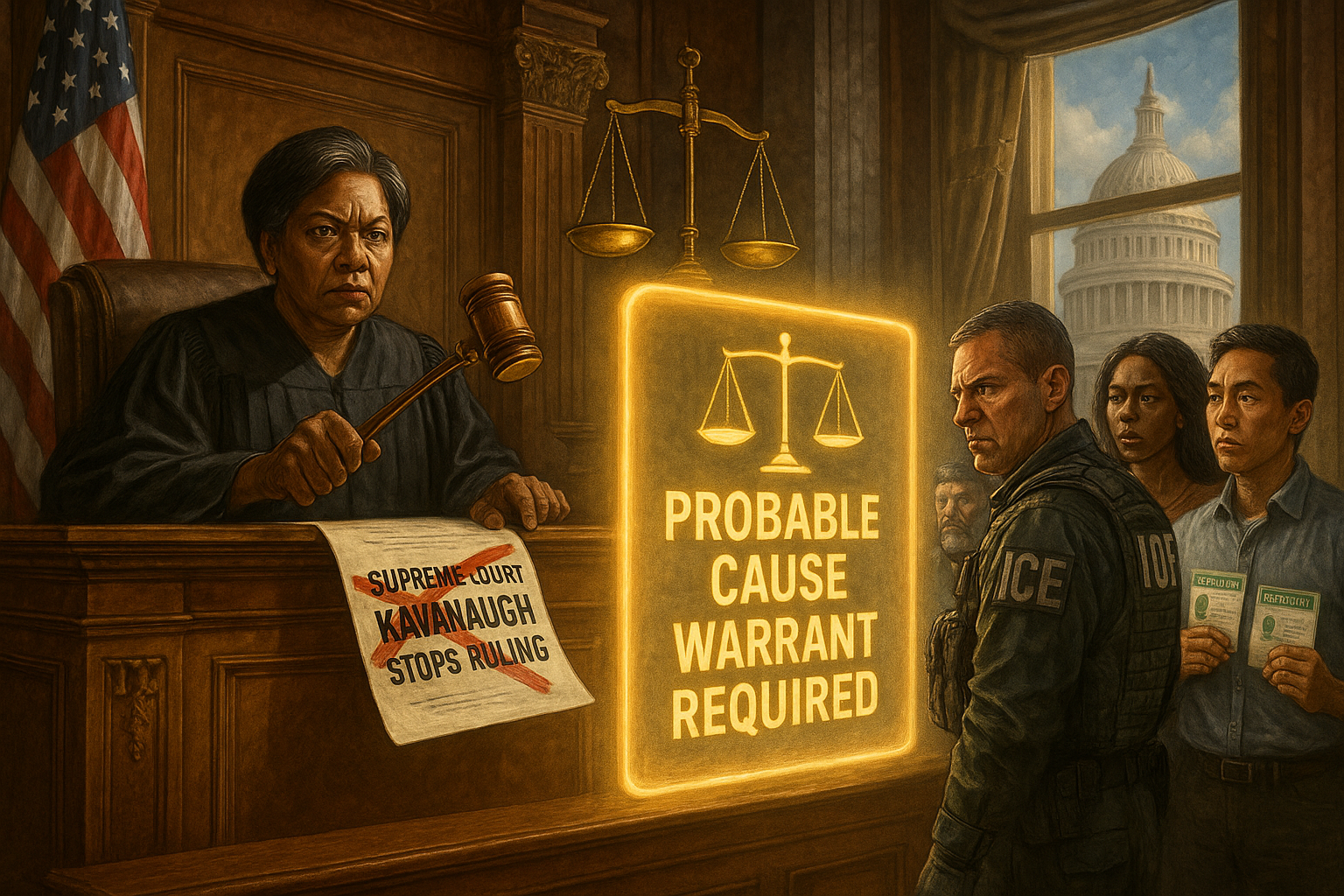

U.S. District Judge Beryl A. Howell has ruled that immigration officers in the District of Columbia must have probable cause before carrying out warrantless arrests, a decision that reins in aggressive enforcement tactics and pointedly questions a recent Supreme Court order that expanded immigration ‘roving patrols’ elsewhere.

On December 3, 2025, U.S. District Judge Beryl A. Howell issued a preliminary injunction limiting when federal immigration agents may conduct warrantless arrests in Washington, D.C., finding that the government had likely violated federal law by detaining migrants without the level of proof required under immigration statutes.

The case was brought by immigrant‑rights group CASA Inc. and several migrants who had been picked up in the city, many of whom had pending immigration applications or other indications they were lawfully present, according to reporting by The Washington Post. The plaintiffs alleged that officers had taken them into custody without warrants and without properly establishing that they were deportable or likely to flee.

Howell’s ruling comes against the backdrop of a September 8, 2025 Supreme Court decision in Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo, in which the justices, by a 6–3 vote, lifted a lower‑court order that had restricted ‘roving’ immigration patrols in the Los Angeles area. In that case, the court’s conservative majority granted the Trump administration’s emergency request to continue stops of people suspected of being in the country illegally, based on factors such as working at a car wash, speaking Spanish or accented English, or having brown skin.

The Supreme Court’s unsigned order offered no reasoning, but Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh issued a 10‑page concurring opinion explaining that, in his view, federal law allows immigration officers to conduct brief investigative stops if they have “reasonable suspicion” that someone is in the United States unlawfully. He wrote that agents could consider the “totality of the circumstances,” including location, type of work, language and, as a “relevant factor,” apparent ethnicity, while stressing that such encounters were supposed to be “brief” inquiries into immigration status.

Civil‑rights advocates quickly dubbed these encounters “Kavanaugh stops,” arguing that they effectively greenlight racial profiling and that, in practice, many of the stops have involved armed raids, use of force, and detentions that last hours or days, as documented in reporting by outlets including the Los Angeles Times, CNBC, and other national and local media.

In her D.C. opinion, Howell distinguished between the brief investigative stops Kavanaugh described and the far more intrusive seizures described by plaintiffs in the Washington case. She noted that the Supreme Court’s order in Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo was a one‑paragraph stay that offered no binding analysis and that Kavanaugh’s concurrence, while more detailed, addressed only the standard for temporary stops, not prolonged detention without a warrant. Without the full Slate opinion text available, related commentary has summarized her view that such an unexplained emergency‑docket order carries limited persuasive weight for the kinds of extended detentions at issue in the capital.

Howell focused instead on the requirements of federal immigration law. According to The Washington Post, she concluded that immigration statutes demand probable cause—rather than mere reasonable suspicion—before officers may arrest and detain a person without an administrative warrant. That showing, she wrote, must establish both that the person is in the country unlawfully and that the individual is likely to escape before a warrant can be obtained. Her injunction directs immigration authorities to document each warrantless arrest in D.C. with “specific, particularized facts” demonstrating probable cause that the person is likely to flee.

The government, however, had repeatedly characterized its authority more broadly. In other public statements about similar operations, Border Patrol Sector Chief Gregory Bovino described enforcement tactics that rely on appearance, language, job type and location in forming reasonable suspicion, and he defended aggressive street sweeps in major cities. Separate coverage of the Los Angeles and Chicago campaigns quoted Bovino as acknowledging that “how they look” can play into enforcement decisions—an example critics say illustrates how race and ethnicity function as proxies under the current approach.

At the policy level, homeland security officials have argued that reasonable‑suspicion standards are sufficient for these kinds of encounters, citing Kavanaugh’s concurrence and the Supreme Court’s emergency ruling. Howell’s decision in D.C. rejects that framing for arrests and continued detention, holding that agents there may not rely on reasonable suspicion alone when they take someone into custody without a warrant.

Data filed in the D.C. case indicate that hundreds of migrants have been seized in the city during recent enforcement surges, the vast majority of whom had no criminal records, according to Washington Post reporting. Howell cited sworn declarations from dozens of migrants describing being picked up without warrants, some while heading to work or medical appointments, in support of her conclusion that the practice was not limited to isolated incidents.

The preliminary injunction does not bar all warrantless immigration arrests in Washington. The judge left room for officers to detain people without warrants if they can document probable cause that an individual is both unlawfully present and at risk of escape. But by requiring such documentation and emphasizing the higher probable‑cause standard, the ruling narrows the gap between how immigration law is written and how it had been applied on the streets of the nation’s capital, and it pushes back against the broader ‘Kavanaugh stop’ paradigm that has taken hold in other parts of the country.