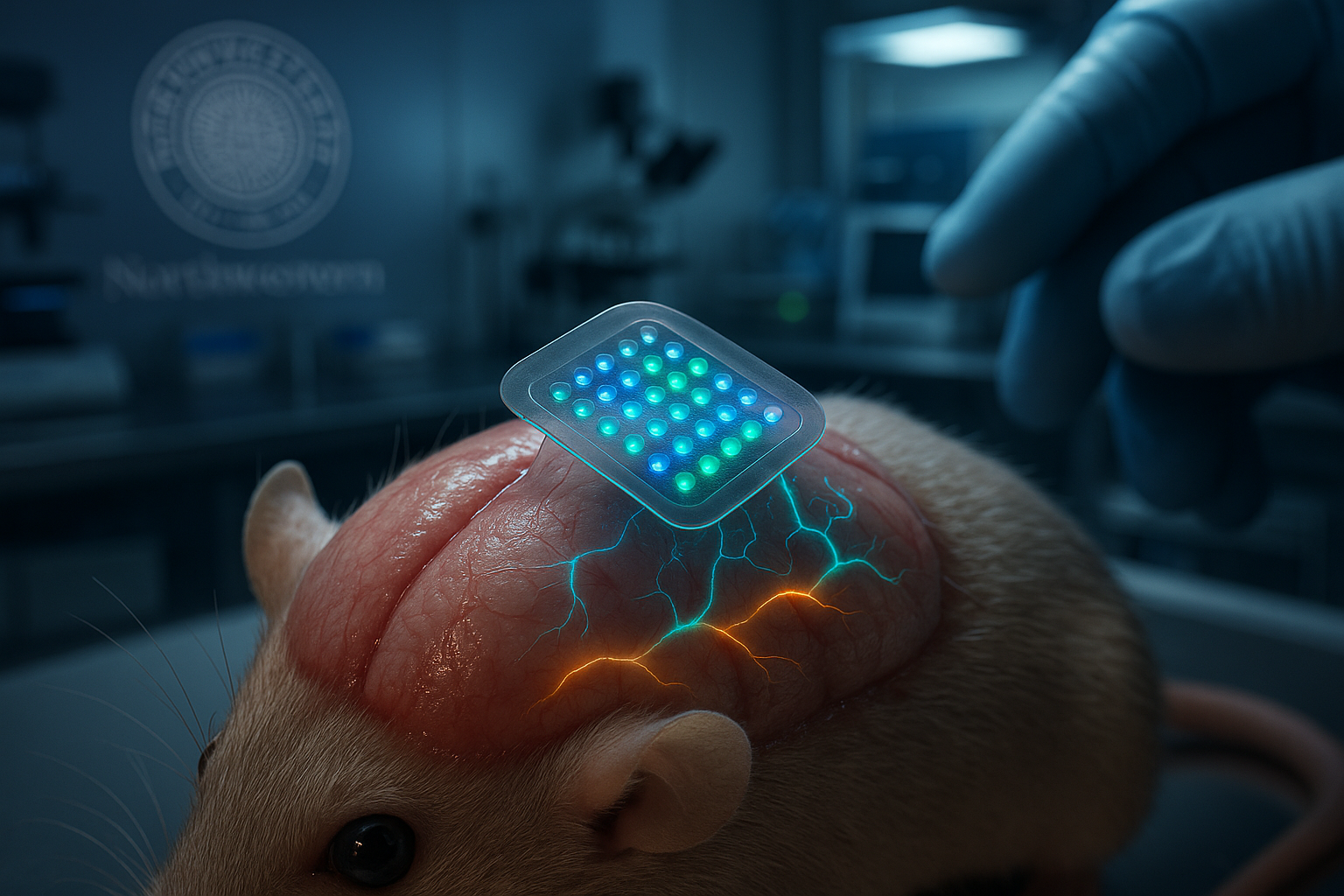

Scientists at Northwestern University have created a soft, wireless brain implant that delivers patterned light directly to neurons, enabling mice to interpret these signals as meaningful cues without relying on sight, sound or touch. The fully implantable device uses an array of up to 64 micro-LEDs to generate complex activity patterns across the cortex, a development that could advance next-generation prosthetics and sensory therapies, according to Northwestern and Nature Neuroscience.

In a major step forward for neurobiology and bioelectronics, researchers led by neurobiologist Yevgenia Kozorovitskiy and bioelectronics pioneer John A. Rogers at Northwestern University have built a fully implantable device that sends information to the brain using light-based signals.

The soft, flexible implant sits under the scalp but on top of the skull, where it delivers precise patterns of light through the bone to activate neurons across the cortex. According to Northwestern, the system uses a programmable array of up to 64 micro-LEDs — each about as small as a human hair — integrated with a wirelessly powered control module to transmit information in real time while remaining completely beneath the skin.

The work, published on December 8, 2025, in the journal Nature Neuroscience under the title "Patterned wireless transcranial optogenetics generates artificial perception," builds on the team’s earlier wireless optogenetics platform, reported in Nature Neuroscience in 2021. That earlier system used a single micro-LED probe to control neurons and influence social behavior in mice, eliminating the need for fiberoptic cables that restricted movement.

In the new study, the device’s array of micro-LEDs is used to generate rich, distributed patterns of activity that more closely resemble the brain’s natural responses during sensory experiences. With real-time control over each LED, researchers can program complex sequences that span multiple cortical regions, mimicking the broad networks activated by real sensations.

“Our brains are constantly turning electrical activity into experiences, and this technology gives us a way to tap into that process directly,” Kozorovitskiy said in a Northwestern news release. “This platform lets us create entirely new signals and see how the brain learns to use them. It brings us just a little bit closer to restoring lost senses after injuries or disease while offering a window into the basic principles that allow us to perceive the world.”

John A. Rogers, who led the technology development, emphasized the goal of a minimally invasive, fully implantable design. “By integrating a soft, conformable array of micro-LEDs — each as small as a single strand of human hair — with a wirelessly powered control module, we created a system that can be programmed in real time while remaining completely beneath the skin, without any measurable effect on natural behaviors of the animals,” he said. “It represents a significant step forward in building devices that can interface with the brain without the need for burdensome wires or bulky external hardware.”

First author Mingzheng Wu noted that the new platform dramatically expands the complexity of patterns that can be delivered to the brain compared with the earlier single-LED device. “In the first paper, we used a single micro-LED,” Wu said. “Now we’re using an array of 64 micro-LEDs to control the pattern of cortical activity. The number of patterns we can generate with various combinations of LEDs — frequency, intensity and temporal sequence — is nearly infinite.”

Physically, the device is roughly the size of a postage stamp and thinner than a credit card, according to Northwestern. Instead of extending probes into brain tissue through a cranial opening, the soft array conforms to the surface of the skull and shines light through the bone. The team uses red light, which penetrates tissue effectively and can reach neurons through the skull.

To test the system, the researchers worked with mice engineered to have light-responsive cortical neurons. Using the implant, they delivered patterned bursts of light across four cortical regions, effectively tapping a code directly into neural circuits. The mice were trained to associate a particular light pattern with a reward that required them to visit a specific port in a behavioral chamber.

Over a series of trials, the animals quickly learned to recognize the target pattern among many alternatives. Even without any visual, auditory or tactile cues, the mice used the artificial signals to choose the correct port and obtain a reward, demonstrating that the brain could interpret the patterned stimulation as meaningful information and use it to guide decisions.

“By consistently selecting the correct port, the animal showed that it received the message,” Wu said. “They can’t use language to tell us what they sense, so they communicate through their behavior.”

Northwestern scientists say the platform could eventually support a range of therapeutic applications, including providing sensory feedback for prosthetic limbs, delivering artificial stimuli for future vision or hearing prostheses, modulating pain perception without opioids or other systemic drugs, aiding rehabilitation after stroke or injury, and enabling control of robotic limbs via brain activity. Those potential uses remain long-term goals; the current study demonstrates the feasibility of encoding artificial perceptions in the brain using patterned light.

The research was supported by the Querrey Simpson Institute for Bioelectronics, the NINDS/BRAIN Initiative, the National Institute of Mental Health and several private foundations, including One Mind, the Kavli Foundation, the Shaw Family, the Simons Foundation, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the Christina Enroth-Cugell and David Cugell Fellowship, according to Northwestern.