Researchers at Arizona State University report that SerpinB3 — a protein better known as a cancer biomarker — plays a natural role in wound repair by spurring skin cells to migrate and rebuild tissue. The peer‑reviewed study appears in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Scientists have long linked SerpinB3 to aggressive cancers. The protein, also called squamous cell carcinoma antigen‑1 (SCCA‑1), was first identified in cervical cancer tissue in 1977 and is used as a serum biomarker in several epithelial cancers. Elevated levels often correlate with advanced disease and treatment resistance.

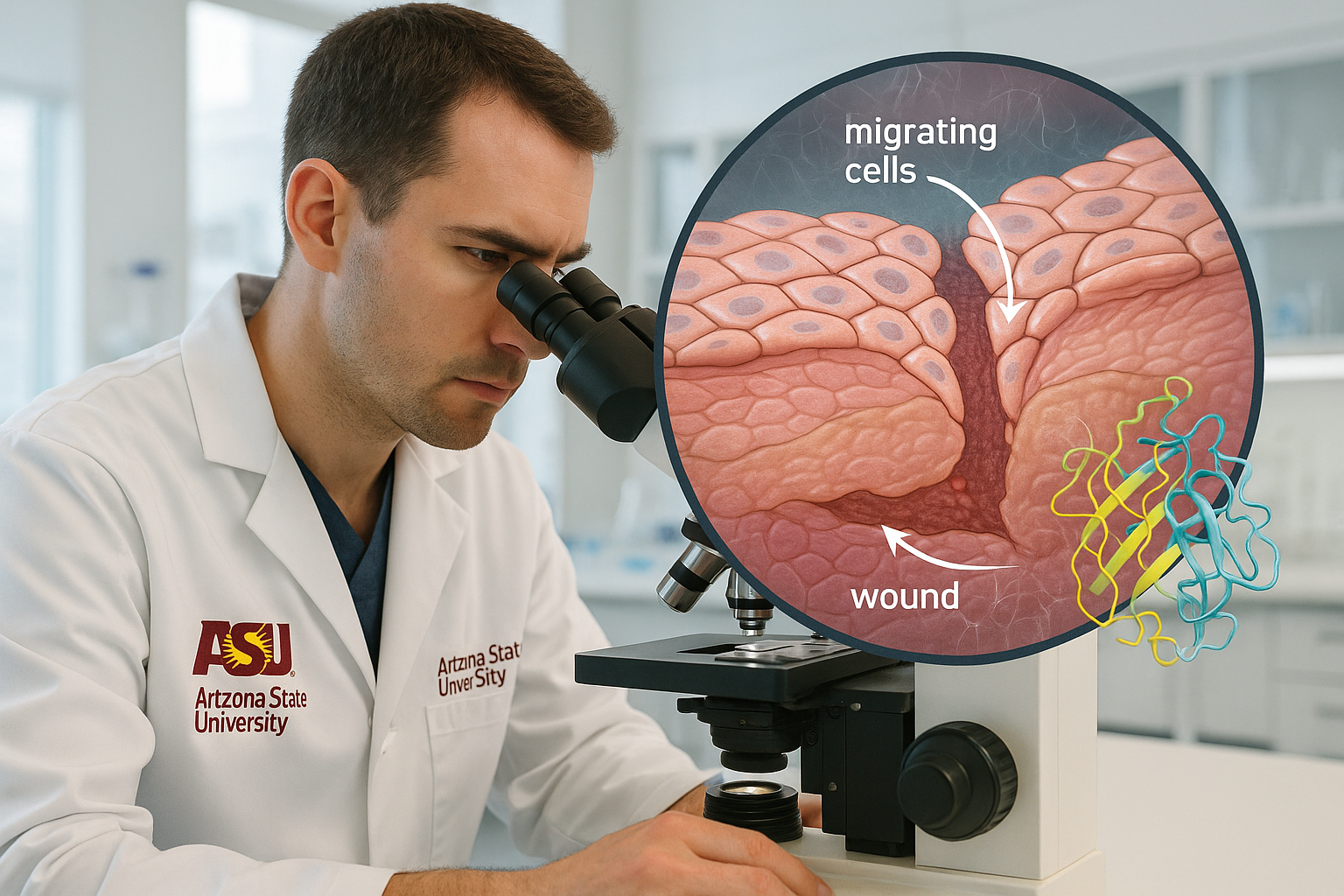

A team at Arizona State University’s Biodesign Center for Biomaterials Innovation and Translation now shows that SerpinB3 is also part of the body’s own wound‑healing toolkit. The research, led by chemical engineering faculty members Jordan R. Yaron and Kaushal Rege, details how SerpinB3 rises in injured skin and helps close wounds by activating keratinocytes — the epidermal cells that move into the wound bed during repair.

The findings were published online October 23, 2025, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (vol. 122, issue 43). In laboratory and animal models, supplying SerpinB3 (or its mouse ortholog, Serpinb3a) accelerated re‑epithelialization and improved the organization of collagen fibers, a structural element important for tissue strength.

“As we looked deeper into how our bioactive nanomaterials were helping tissue repair, SerpinB3, a protein originally implicated in cancer, jumped at us as a key factor that correlated with nanomaterial‑driven wound healing,” said Rege, a professor of chemical engineering and director of the center. “This journey, which started from use‑inspired research on biomaterials for tissue repair to uncovering the fundamental role of this protein as an injury‑response mechanism in skin, has been truly fascinating. We are now building on this basic finding and investigating the role of SerpinB3 in other pathological conditions.”

In cell assays, SerpinB3 promoted faster coverage of scratch wounds by keratinocytes and performed about as effectively as epidermal growth factor, a well‑known pro‑healing signal. In skin wounds, the protein also supported broader repair programs, with treated tissue showing more orderly collagen architecture. The team further observed that wounds covered with advanced biomaterial dressings exhibited a stronger surge of SerpinB3, consistent with earlier work showing such materials can amplify endogenous repair cues.

“For more than four decades, SerpinB3 has been recognized as a driver of cancer growth and metastasis — so much so that it became a clinical diagnostic. Yet after all this time, its normal role in the body remained a mystery,” said Yaron. “But when we looked at injured, healing skin, we found that cells moving into the wound bed were producing enormous amounts of this protein. It became clear that this is part of the machinery humans evolved to heal epithelial injuries — a process that cancer cells have learned to exploit to spread.”

Chronic wounds remain a major burden, with an estimated 6 million occurring annually in the United States and costing roughly $20 billion. By illuminating SerpinB3’s physiological role, the study suggests two translational paths: boosting the protein to aid difficult‑to‑heal wounds, or limiting its activity to help counter cancer. Because SerpinB3 is part of the broader serpin family — regulators of processes such as blood clotting and immune responses — the authors note that additional research is needed to map how it coordinates with other repair pathways and to evaluate therapeutic strategies in clinical settings.