Researchers at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center have found that certain macrophages, a type of immune cell, can form rapid, neuron-like connections with muscle fibers to speed healing. By delivering quick pulses of calcium into damaged muscle, these cells trigger repair-related activity within seconds. The findings, published online November 21, 2025, in Current Biology, could eventually inform new treatments for muscle injuries and degenerative conditions.

Muscle repair varies depending on the type of damage, from acute sports injuries to chronic conditions such as muscular dystrophy. A research team at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center has identified a shared mechanism that appears to enhance recovery across multiple forms of muscle damage.

The study, published online November 21, 2025, in Current Biology, was led by first author Gyanesh Tripathi, PhD, and corresponding author Michael Jankowski, PhD, who leads the Research Division in Cincinnati Children's Department of Anesthesia and serves as Associate Director of Basic Science Research for the Pediatric Pain Research Center.

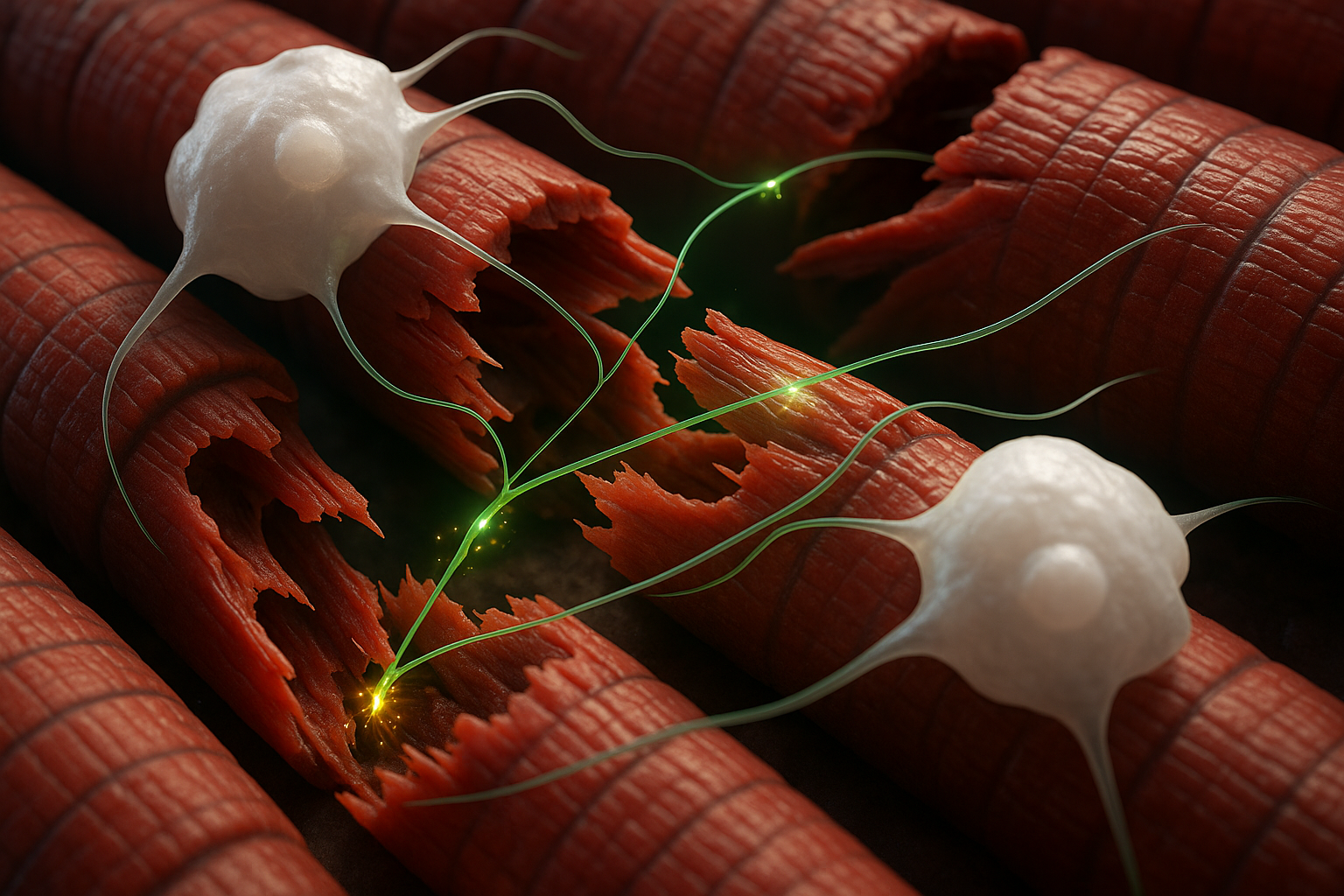

The newly identified process centers on macrophages, an immune cell type best known for clearing bacteria, dead cells and other debris. According to Cincinnati Children's, the team found that specific infiltrating macrophages can form synaptic-like contacts with myofibers, the muscle cells that make up skeletal muscle tissue.

The discovery emerged from work originally aimed at easing post-surgical pain. Instead of a new pain-relief strategy, the researchers observed a surprisingly fast repair response.

In mouse models of two forms of muscle damage—acute incision and more severe injury, including disease-like damage—brief chemogenetic activation of macrophages with a designer compound prompted the cells to release calcium ions directly to nearby muscle fibers. Within about 10 to 30 seconds, the researchers recorded calcium transients and low-level electrical activity in the injured muscle, accompanied by subtle muscle twitches.

"This occurs in a very rapid fashion. You can activate the macrophage and make the muscle twitch subtly almost immediately," Jankowski said, according to materials from Cincinnati Children's. The study reports that the effect involves infiltrating macrophages that arrive after damage, rather than resident immune cells already in the tissue.

In mouse models mimicking muscular dystrophy–like muscle damage, the same type of macrophage-driven signaling helped organize immune cells at injury sites and triggered waves of activity in affected muscle fibers. After 10 days, mice receiving macrophage activation showed substantially more new muscle fibers than control animals, the authors reported.

"The biggest surprise about this was finding that a macrophage has a synaptic-like property that delivers an ion to a muscle fiber to facilitate its repair after an injury," Jankowski said in a statement released by Cincinnati Children's. "It's literally like the way a neuron works, and it's working in an extremely fast synaptic-like fashion to regulate repair."

Despite the accelerated healing response, the experiments did not reveal a corresponding reduction in acute pain. The researchers note that understanding why about 20% of children who undergo surgery continue to experience longer-term pain could be an important next step.

Future work will explore whether human macrophages display similar synaptic-like behavior and whether such cells could be used as delivery vehicles for additional therapeutic signals or materials. Co-authors on the study include Adam Dourson, PhD, Fabian Montecino-Morales, PhD, Jennifer Wayland, MS, Sahana Khanna, Megan Hofmann, Hima Bindu Durumutla, MS, Thirupugal Govindarajan, PhD, Luis Queme, MD, PhD, and Douglas Millay, PhD. The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Research Foundation.