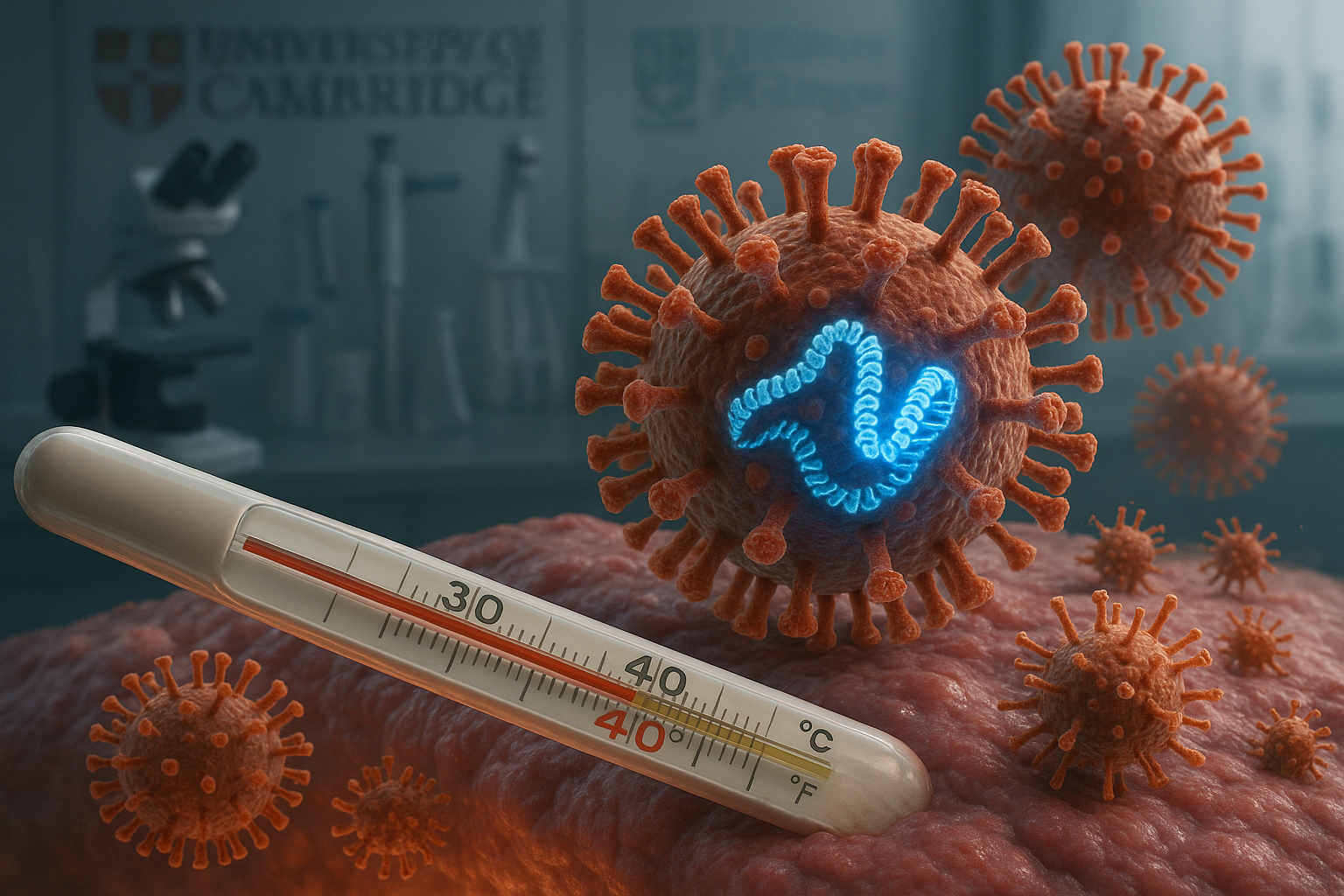

Scientists from the universities of Cambridge and Glasgow have shown why many bird flu viruses can keep replicating at fever-like temperatures that typically curb human flu. A study in Science identifies the viral PB1 gene as crucial to this heat tolerance, raising concerns about pandemic risks if such genes move into human strains.

New research led by scientists at the University of Cambridge and the University of Glasgow identifies a crucial advantage of many avian influenza viruses: they can continue to multiply at body temperatures that normally help the immune system suppress human influenza A viruses.

Published on November 28, 2025, in the journal Science, the study reports that a gene known as PB1 plays a central role in determining how sensitive influenza A viruses are to heat. According to summaries from the University of Cambridge and ScienceDaily, PB1 helps explain why bird flu viruses can replicate even at fever-level temperatures that typically inhibit human-adapted strains.

Seasonal human influenza A viruses generally replicate most efficiently in the cooler upper airways, where temperatures are around 33°C, and are less effective in the warmer lower respiratory tract, closer to 37°C. Fever, which can raise core body temperature up to about 41°C, is one of the body's natural defences against viral infections.

By contrast, avian influenza viruses are adapted to hotter environments. In their natural bird hosts, such as ducks and seagulls, they often infect the gut, where temperatures can reach 40–42°C. The new work helps explain why these viruses are less affected when they cross into mammals, whose fevers do not necessarily stop avian-origin strains.

To investigate this, the researchers simulated fever conditions in mice infected with influenza viruses. Because mice do not typically develop fever in response to influenza A infection, the team raised the ambient temperature in the animals' housing to increase their body temperature. They used a well-characterised, laboratory-adapted human-origin influenza A strain known as PR8, which does not pose a risk to people.

The experiments showed that elevating body temperature to fever levels was highly effective at blocking replication of human-origin flu viruses and protecting against severe disease. A rise of about 2°C was enough to turn what would otherwise be a lethal infection with the PR8 strain into a mild illness in mice. However, similar temperature increases did not stop avian influenza viruses, which continued to replicate and caused severe disease.

Further analysis revealed that PB1, a gene essential for copying the viral genome inside infected cells, is a key determinant of temperature sensitivity. Viruses carrying an avian-like PB1 gene withstood the high temperatures associated with fever and still caused serious illness in mice. According to the Cambridge and Glasgow releases, this is important because influenza A viruses from birds and humans can swap genes when they co-infect the same host, such as pigs.

During the major influenza pandemics of 1957 and 1968, a PB1 gene of avian origin moved into circulating human influenza viruses. The new study suggests that this kind of gene reassortment can confer heat tolerance, potentially making pandemic strains more capable of spreading despite fever responses.

Dr Matt Turnbull, the study's first author from the Medical Research Council Centre for Virus Research at the University of Glasgow, said in a university statement: "The ability of viruses to swap genes is a continued source of threat for emerging flu viruses. We've seen it happen before during previous pandemics, such as in 1957 and 1968, where a human virus swapped its PB1 gene with that from an avian strain. This may help explain why these pandemics caused serious illness in people.

"It's crucial that we monitor bird flu strains to help us prepare for potential outbreaks. Testing potential spillover viruses for how resistant they are likely to be to fever may help us identify more virulent strains."

Senior author Professor Sam Wilson, from the Cambridge Institute of Therapeutic Immunology and Infectious Disease at the University of Cambridge, noted that bird flu infections in people remain relatively rare but can be severe. He said, according to the Cambridge release: "Thankfully, humans don't tend to get infected by bird flu viruses very frequently, but we still see dozens of human cases a year. The authors show that replication of human-adapted influenza virus is attenuated when temperatures are increased, such as in a fever. But avian influenza viruses, whose natural hosts have higher body temperatures, are not controlled by the fever response when they cross into mammals.

"They link their findings to one particular gene of the virus, called PB1, which is often carried over from birds when a new pandemic virus emerges. These findings have important implications for when and how to use drugs to control the fever that is associated with an influenza infection, and may also help us to understand why the disease from some influenza outbreaks is more severe."

Public health agencies have previously reported that certain avian H5N1 infections in humans have had fatality rates exceeding 40 percent, though such cases have been rare and typically linked to close contact with infected birds or contaminated environments.

The study's authors and institutional statements caution that more research is needed before changing clinical guidance on fever treatment. Some existing clinical evidence suggests that routinely suppressing fever with common antipyretic medications, such as ibuprofen or aspirin, may not always benefit patients and could, in some circumstances, support influenza A virus spread. The new work adds a mechanistic explanation for why fever can be protective against human-origin strains while offering less protection against avian-origin viruses.

The research was funded primarily by the UK's Medical Research Council, with additional support from the Wellcome Trust, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the European Research Council, the European Union's Horizon 2020 programme, the UK Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, and the US Department of Agriculture.

Overall, the findings highlight the need to monitor bird flu viruses not only for mutations that affect transmission but also for genetic traits, such as PB1-linked heat resistance, that could undermine one of the body's key innate defences against infection.