A Texas A&M University team has developed a biodegradable microneedle patch that delivers interleukin‑4 directly to damaged heart tissue after a heart attack. In preclinical models, this targeted approach shifts immune cells into a healing mode and improves communication between heart muscle and blood vessel cells, while avoiding many of the side effects seen with systemic drug delivery.

Heart attacks deprive heart muscle cells of oxygen and nutrients, leading to cell death and the formation of scar tissue. While this scarring helps stabilize the damaged area, it cannot contract like healthy muscle, forcing the remaining heart tissue to work harder and potentially contributing to heart failure over time.

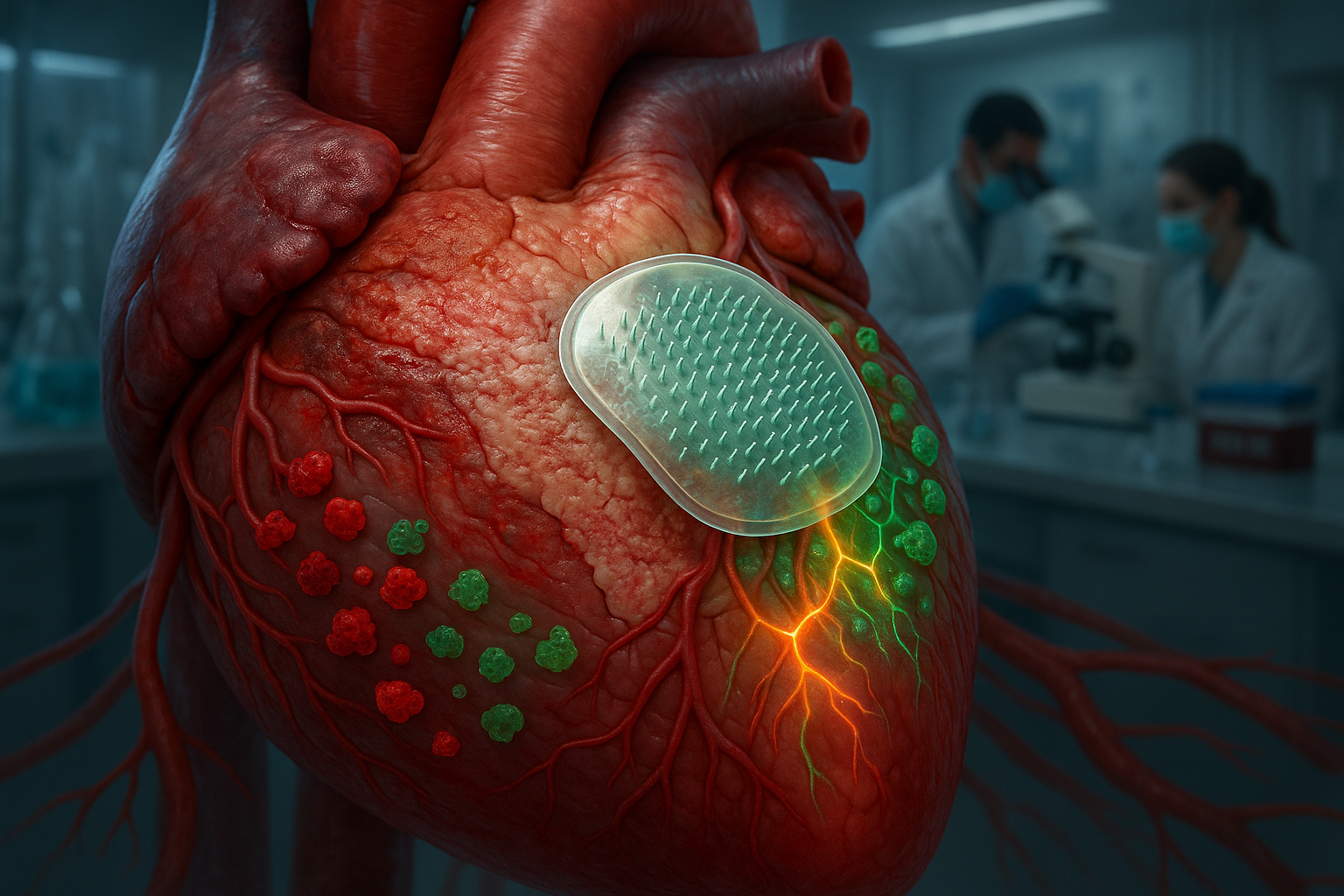

To address this, a team led by Dr. Ke Huang at Texas A&M University has created a biodegradable microneedle patch that delivers interleukin‑4 (IL‑4), a molecule known for regulating immune responses, directly to injured cardiac tissue. Each tiny needle in the patch contains microscopic particles loaded with IL‑4. When the patch is applied to the surface of the heart, the microneedles penetrate the outer layer and dissolve, releasing the drug into the damaged muscle underneath, according to Texas A&M’s release.

By concentrating IL‑4 at the site of injury, the patch encourages macrophages — key immune cells — to shift from a pro‑inflammatory state to a reparative one. This change helps limit excessive scar formation and supports better functional recovery in the preclinical models described. “Macrophages are the key,” Huang said in the university’s announcement. “They can either make inflammation worse or help the heart heal. IL‑4 helps turn them into helpers.”

Previous attempts to use IL‑4 to repair heart tissue relied on injections into the bloodstream, which circulated the molecule throughout the body and led to unwanted effects in other organs. The localized microneedle approach is designed to focus treatment on the heart while minimizing systemic exposure. “Systemic delivery affects the whole body,” Huang said. “We wanted to target just the heart.”

The study team also reported notable changes in how treated heart muscle cells, or cardiomyocytes, behaved after patch application. In laboratory and animal studies, cardiomyocytes became more responsive to signals from surrounding tissues, particularly endothelial cells lining blood vessels. Huang said this enhanced cell‑to‑cell communication appeared to support recovery. “The cardiomyocytes weren’t just surviving, they were interacting with other cells in ways that support recovery,” he noted.

Researchers observed that the patch reduced inflammatory signals from endothelial cells, which can otherwise worsen damage after a heart attack. They also detected increased activity in a signaling route known as the NPR1 pathway, which is associated with blood vessel health and overall heart function.

At present, placing the patch requires open‑chest surgery in the animal models used. Huang and his colleagues say they hope to adapt the technology for minimally invasive delivery in the future, envisioning a version that could be inserted through a small tube to make it more practical in clinical settings.

The work, funded by the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association, was published in the journal Cell Biomaterials. The study, which tested the patch in rodent and porcine models of myocardial infarction, is an early‑stage, proof‑of‑concept effort and is not yet available as a treatment for patients.

Looking ahead, Huang is collaborating with Xiaoqing (Jade) Wang, an assistant professor of statistics in Texas A&M’s College of Arts and Sciences, on an artificial intelligence model to map immune responses and guide future immunomodulatory therapies. “This is just the beginning,” Huang said. “We’ve proven the concept. Now we want to optimize the design and delivery.”