Researchers at the Ruđer Bošković Institute in Zagreb report that the protein CENP-E plays a crucial role in stabilizing the earliest attachments between chromosomes and microtubules during cell division, rather than mainly acting as a motor that pulls chromosomes into place. The work, described in two studies in Nature Communications, revises long-standing models of chromosome congression by linking CENP-E’s function to Aurora kinases and suggesting implications for understanding diseases marked by chromosome segregation errors.

Cell division requires precise chromosome alignment so that each daughter cell receives an accurate copy of genetic material. Errors in this process can lead to infertility, developmental disorders and cancer, a connection widely documented in cell biology research.

For nearly two decades, the dominant model held that CENP-E, a kinetochore motor protein, transported misaligned chromosomes toward the center of the cell’s spindle largely by gliding them along microtubules. Recent work by a team led by Dr. Kruno Vukušić and Professor Iva M. Tolić at the Ruđer Bošković Institute challenges this view.

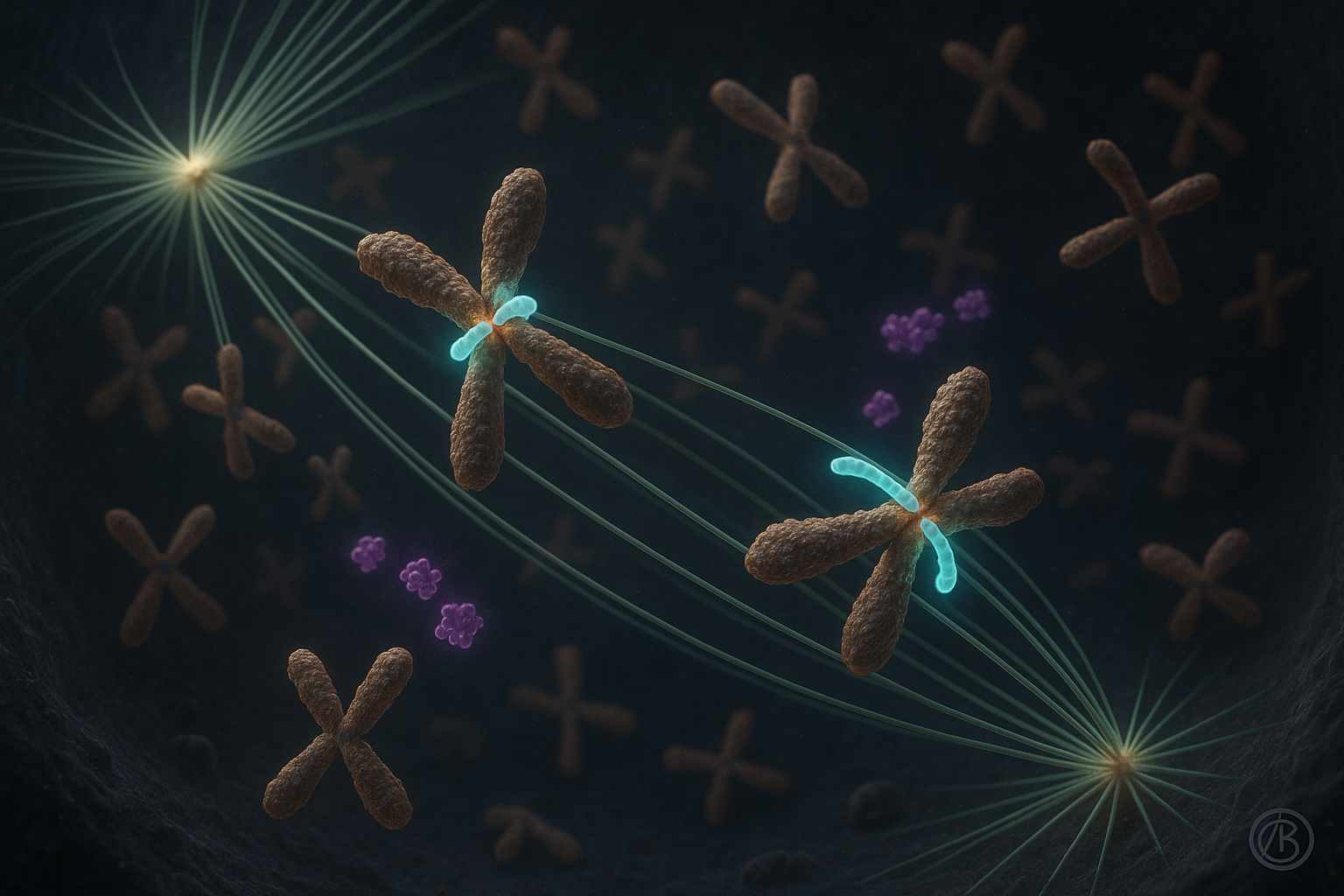

In one of the new Nature Communications papers, the authors report that CENP-E is essential for initiating chromosome congression by promoting and stabilizing end-on attachments between kinetochores and microtubules, especially for chromosomes that start near the spindle poles. Once these stable attachments form and biorientation is established, the subsequent movement of chromosomes toward the spindle equator proceeds with similar dynamics regardless of CENP-E activity, according to the study.

The research further shows that Aurora A and Aurora B kinases act as inhibitors of this initiation step when CENP-E is absent or inactive, in part by driving hyperphosphorylation of microtubule-binding proteins and maintaining an expanded fibrous corona at kinetochores. CENP-E counteracts Aurora B–mediated phosphorylation in a BubR1-dependent manner, helping to stabilize initial end-on attachments and trigger the transition from lateral to end-on binding.

A companion Nature Communications article from the same group extends this picture by proposing a feedback loop between centrosomes and kinetochores in which Aurora A activity near spindle poles enhances Aurora B at kinetochores, thereby limiting the start of congression when CENP-E is not functional. Removing centrioles or inhibiting Aurora A relaxes this brake and can permit congression to begin even without active CENP-E, the authors report.

Together, the studies suggest that chromosome congression unfolds in at least two biomechanical phases: an initiation phase that depends strongly on CENP-E’s ability to stabilize end-on attachments in the face of Aurora kinase activity, and a subsequent movement phase dominated by spindle geometry and microtubule dynamics rather than by CENP-E–driven transport.

The findings revise a force-focused description that has appeared in textbook models of mitosis, replacing it with a regulatory framework in which CENP-E, Aurora kinases, BubR1 and other kinetochore components coordinate the timing and location of stable microtubule attachments. According to a summary from the Ruđer Bošković Institute, by clarifying how these molecular regulators cooperate, the work helps explain how cells maintain high fidelity during division and may inform future research into cancers and other conditions where chromosome segregation is frequently disrupted.

Both studies were carried out at the Ruđer Bošković Institute and supported by European Research Council grants and national Croatian funding, and they relied on advanced live-cell imaging and computational analysis to track chromosome behavior and molecular signaling during mitosis.