Scientists at Moffitt Cancer Center report developing a computational method, ALFA-K, that uses longitudinal single-cell measurements to infer how gains and losses of whole chromosomes can shape a tumor’s evolutionary path. The work, published in Nature Communications, argues that these large-scale chromosome changes follow measurable patterns influenced by cellular context and treatment-related stress rather than unfolding as pure randomness.

Cancer can evolve quickly when cells gain or lose whole chromosomes—large-scale changes that alter the dosage of many genes at once and can reshape how a tumor grows and responds to stress.

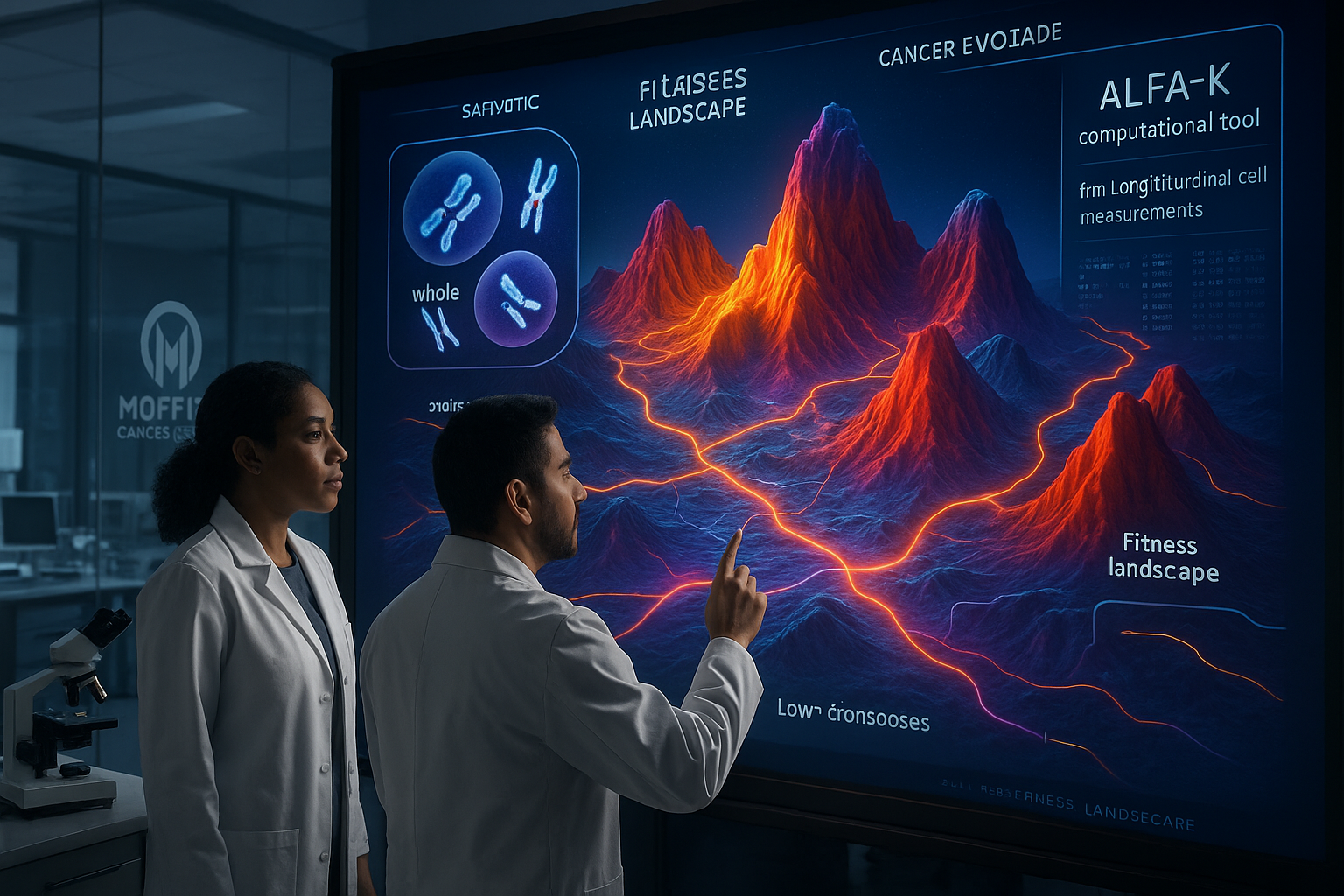

Researchers at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute describe a new computational approach, called ALFA-K (Adaptive Local Fitness landscapes for Aneuploid Karyotypes), that aims to predict how such chromosome-level changes accumulate over time. The team says ALFA-K is designed for longitudinal single-cell data, allowing it to reconstruct how cancer cell populations move through different chromosome “states” and to estimate which chromosome combinations appear favored under selection pressures, including treatment-related stress.

In a Q&A accompanying the release, corresponding author Noemi Andor said the goal was to move beyond one-time snapshots of tumor genetics and quantify which chromosome combinations help cells persist. “Cancer evolves. As tumors grow, their cells constantly make mistakes when copying and dividing their DNA. Many of those mistakes involve gaining or losing whole chromosomes,” Andor said.

According to the researchers, ALFA-K differs from earlier approaches that often treated individual chromosome gains or losses as having fixed effects. Instead, it models context dependence—the same chromosome change may be advantageous or harmful depending on the cell’s existing chromosome makeup—and incorporates ongoing chromosomal instability.

In the study, the team reports estimating fitness across more than 270,000 distinct chromosome configurations, and concludes that environmental conditions and cisplatin treatment can change the fitness impact of chromosome copy-number shifts. The analysis also highlights whole-genome doubling—when a cell duplicates all its chromosomes—as a mechanism that can buffer some of the harms of extreme chromosomal instability, with the researchers describing a threshold beyond which genome doubling becomes evolutionarily advantageous.

The paper lists Richard J. Beck, Tao Li and Noemi Andor as authors and was published online in Nature Communications in late December 2025. The work was supported by the U.S. National Cancer Institute, including grants 1R37CA266727-01A1, 1R21CA269415-01A1, and 1R03CA259873-01A1.

The researchers say that, in the long run, tools like ALFA-K could support “evolution-aware” treatment strategies—using repeat sampling such as biopsies to identify when tumors may be approaching risky evolutionary transitions and to select therapies intended to limit routes to drug resistance.