A day after President Donald Trump said major U.S. oil companies would spend “billions and billions” to repair Venezuela’s battered oil infrastructure following the U.S. capture of President Nicolás Maduro, energy analysts cautioned that restoring output would likely take years and depend on political stability, contract protections and the economics of producing and refining the country’s extra-heavy crude.

Venezuela has the world’s largest proven crude oil reserves—about 303 billion barrels, roughly 17% of the global total, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. But production has collapsed from more than 3 million barrels per day at its peak to roughly around 1 million barrels per day in recent years—less than 1% of global supply—after years of underinvestment, operational decline and U.S.-led sanctions.

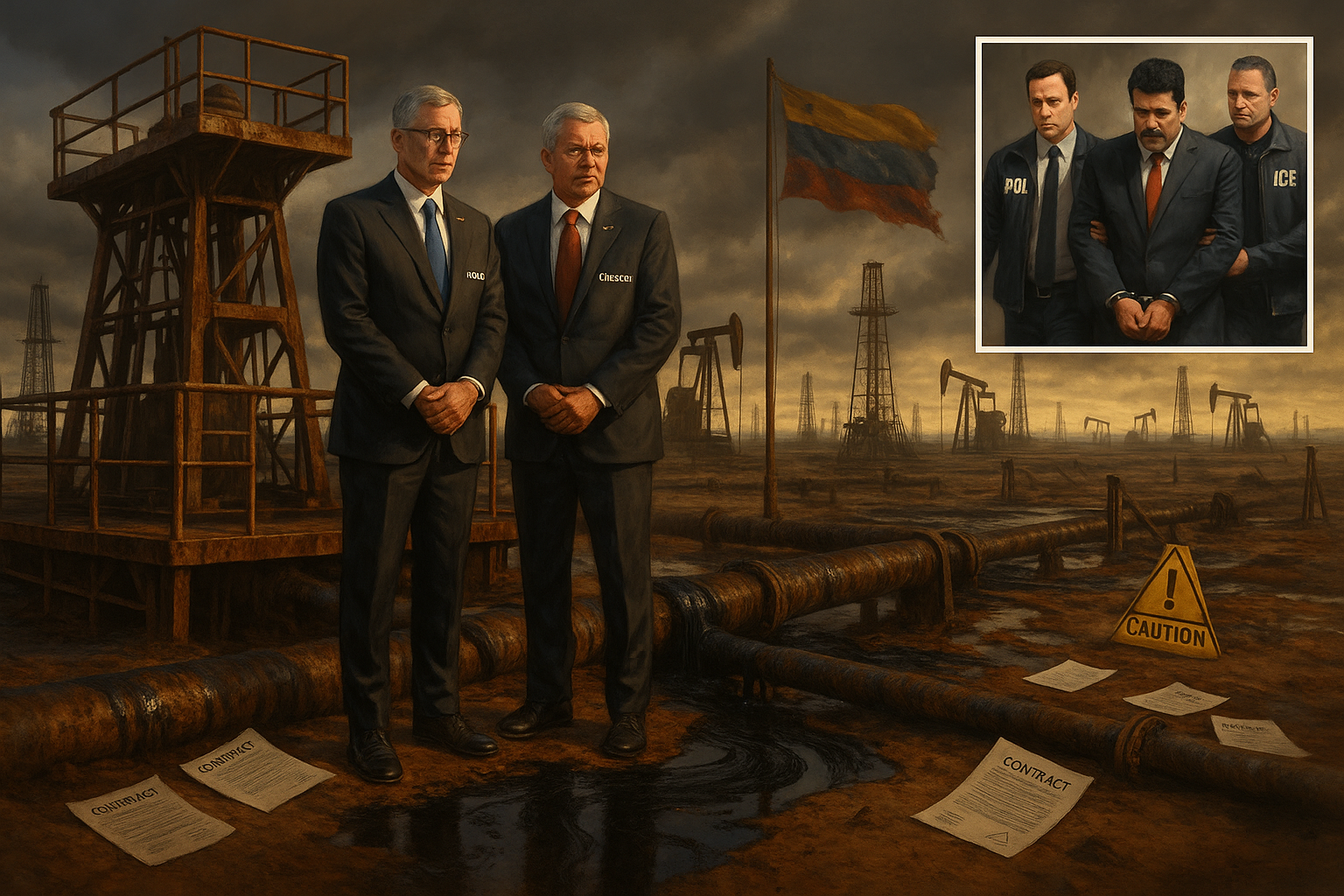

Trump, speaking January 3 at Mar-a-Lago, said U.S. oil companies would “go in, spend billions of dollars” and fix Venezuela’s “badly broken” oil infrastructure, adding that companies would be “reimbursed.” Oil companies have not publicly committed to new investments. In statements cited by multiple outlets, Chevron said it would comply with relevant laws and regulations, and industry observers noted that large-scale re-entry would require clear legal protections and security assurances.

Venezuela’s crude is largely extra-heavy and high in sulfur, concentrated in the Orinoco Belt. That makes it more expensive to produce and requires blending or specialized refining capacity. In recent years, U.S. sanctions shifted much of Venezuela’s crude exports toward China, where independent refiners and intermediaries have taken discounted cargoes. Analysts say a sanctions shift could reroute barrels back to U.S. Gulf Coast refineries that were built to process heavy grades, but that would not by itself solve Venezuela’s deeper operational problems.

Chevron is the only major U.S. oil company that has maintained a presence in Venezuela in recent years under U.S. authorizations, and its joint ventures have at times accounted for roughly a quarter of Venezuela’s output, according to reporting by CNBC and Bloomberg. Other U.S. producers have long, contentious histories in Venezuela. Exxon Mobil and ConocoPhillips exited during the country’s contract overhauls and nationalization drive under President Hugo Chávez, later prevailing in international arbitration to varying degrees; the pace and scale of any repayments have differed across cases and have often been partial.

Even if sanctions are loosened, analysts warned that the investment case is uncertain. Global oil markets have been relatively well supplied, and forecasts cited by Reuters put benchmark prices in the low-to-mid $50s per barrel range for 2026. At those levels, Venezuela’s heavy oil projects—often capital-intensive and technically complex—can be difficult to justify without highly favorable fiscal terms and stable operating conditions.

Neighboring Guyana, by contrast, has attracted major investment led by Exxon Mobil as it ramps up offshore production of lighter crude under widely viewed investor-friendly terms, though its development has also been shadowed by a long-running territorial dispute between Guyana and Venezuela.

Consultancies including Wood Mackenzie have argued that Venezuela could raise output relatively quickly by repairing wells and improving day-to-day operations if sanctions were lifted and operational and financial support returned. But analysts also say sustaining a larger recovery would require major new investment—potentially tens of billions of dollars—and years of work rebuilding decayed infrastructure and restoring skilled capacity across the industry.

For now, the immediate outlook remains dominated by politics. With Maduro’s capture and uncertainty over Venezuela’s leadership and governance, energy executives and analysts say companies are likely to insist on clear contract enforceability and security guarantees before committing significant new capital—conditions that may take time to establish even under an internationally backed transition.