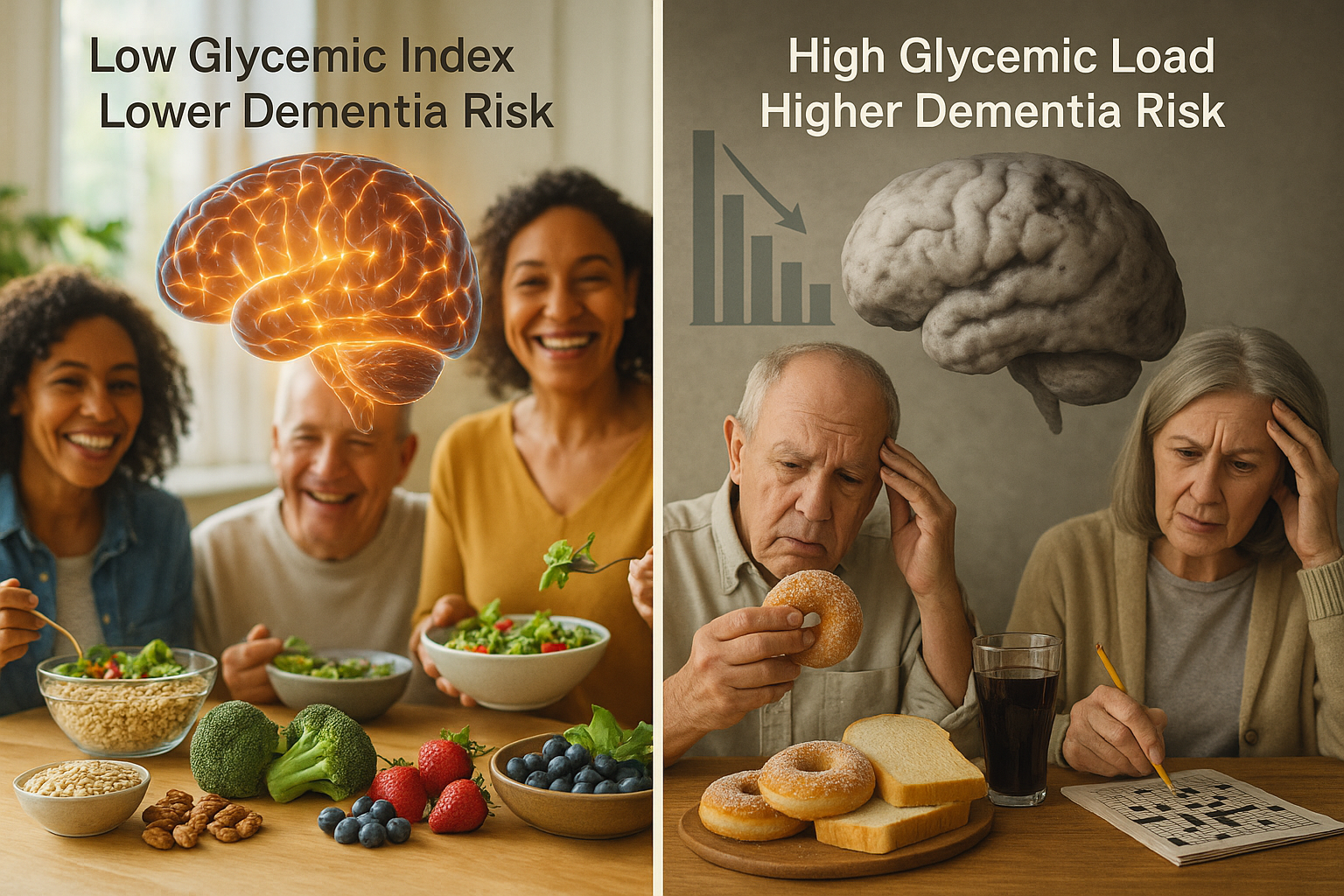

A long-term analysis of more than 200,000 UK Biobank participants found that diets with lower glycemic index values were associated with a lower risk of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia, while higher dietary glycemic load was tied to a higher risk.

A study led by researchers at Universitat Rovira i Virgili (URV) and affiliated institutes reports that the quality and quantity of dietary carbohydrates—measured using the glycemic index (GI) and glycemic load (GL)—may be associated with the risk of developing dementia.

The research, published in the International Journal of Epidemiology, analyzed 202,302 UK Biobank participants who were free of dementia at baseline. Dietary GI and GL were estimated using the Oxford WebQ, a 24-hour, web-based dietary questionnaire. Participants were followed for an average of 13.25 years, during which 2,362 developed dementia, according to a university summary of the study.

GI is a scale that ranks carbohydrate-containing foods based on how quickly they raise blood glucose after eating. The researchers reported that foods such as white bread and potatoes tend to score higher, while whole grains and many fruits score lower.

In the peer-reviewed analysis, GI showed a nonlinear relationship with dementia risk. After accounting for potential confounders, the researchers found that GI values below an identified inflection point (49.30) were associated with a lower risk of dementia (hazard ratio 0.838; 95% CI 0.758–0.926). GL showed the opposite pattern: GL values above an inflection point (111.01) were associated with a higher risk (hazard ratio 1.145; 95% CI 1.048–1.251). The paper reported broadly similar patterns for Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia.

In a URV statement distributed via ScienceDaily, study leader Mònica Bulló said the results suggest that diets emphasizing low-GI foods—such as fruit, legumes and whole grains—could help reduce the risk of cognitive decline and dementia. The researchers also highlighted that carbohydrates typically contribute about 55% of daily energy intake, underscoring why carbohydrate quality and quantity may matter for metabolic health and conditions linked to brain function.

The authors cautioned that the findings are observational and indicate associations rather than proof that changing dietary GI or GL will prevent dementia. Still, they argued that the results support considering both carbohydrate quality and quantity in dietary approaches aimed at healthier aging.