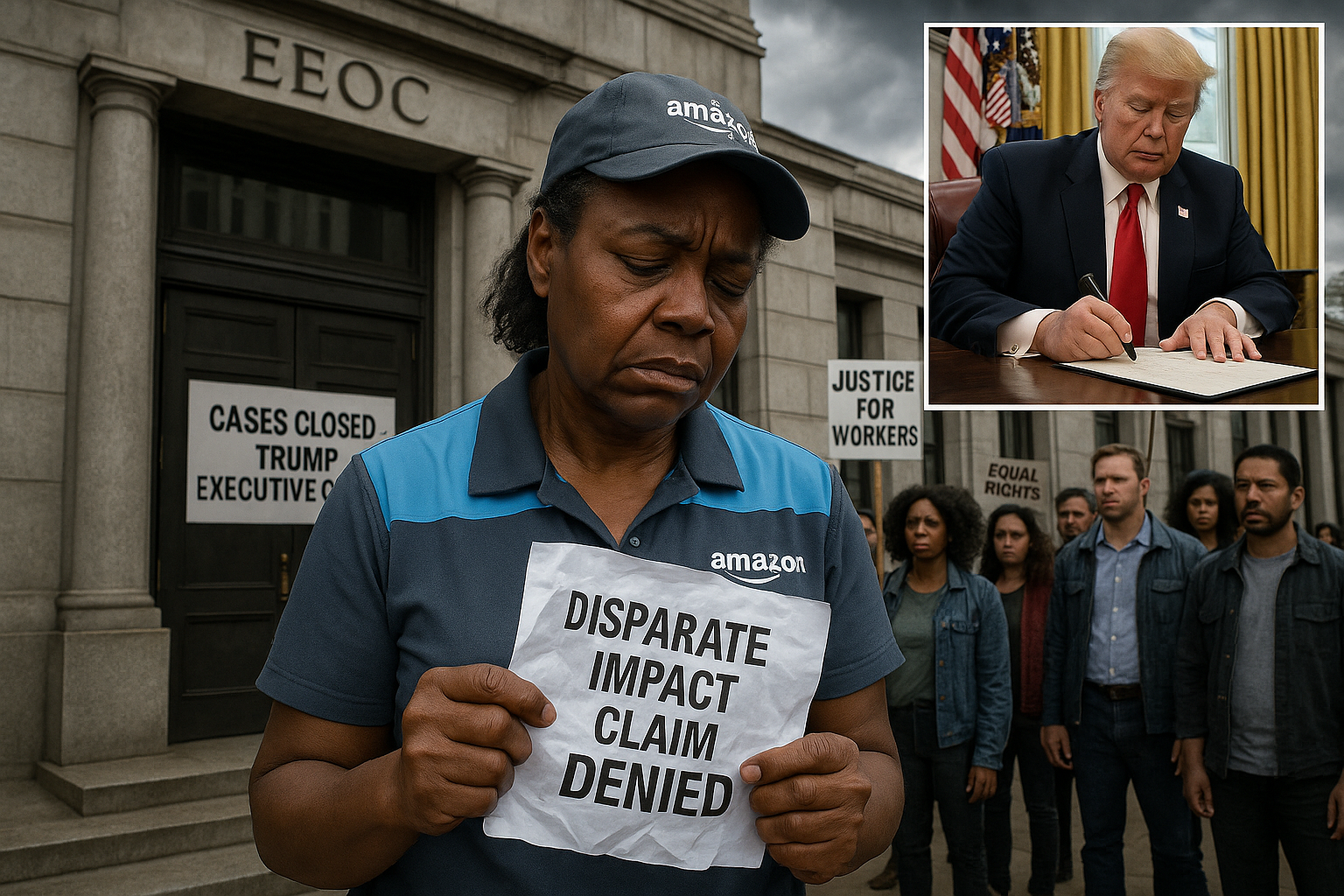

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has begun closing disparate impact discrimination cases following an executive order from President Donald Trump that directs federal agencies to deprioritize that legal theory. The shift, which legal experts say conflicts with long-standing precedent under Title VII, has left workers like former Amazon delivery driver Leah Cross without the usual federal backing for claims that facially neutral policies have discriminatory effects.

In August 2022, just after Prime Day, Leah Cross began working as an Amazon delivery driver in Colorado. She told The Nation she took the job expecting decent pay and benefits from what she viewed as a reputable company, but soon encountered demanding quotas and intense monitoring.

Cross said Amazon assigned her routes with more than 200 stops a day on 10-to-12-hour shifts. Each stop could involve multiple deliveries, and she was monitored by cameras in the delivery van. If she fell behind schedule, supervisors called to check on her progress, leaving, she said, little room for breaks.

Early in her employment, Cross stopped to buy menstruation products and received a disciplinary call from a dispatch officer, according to her account to The Nation. She said that while she ultimately received only a verbal warning, the incident underscored how little time drivers felt they had for basic needs. Bathroom breaks, she recalled, became especially difficult: if she pulled over to use a restroom along her route, she would receive calls from supervisors asking where she was and whether she was lost.

Cross told The Nation that higher‑ups indicated she would need to purchase "devices" to meet the quotas. She ultimately bought a funnel so she could urinate into a bottle in the back of her van, out of view of cameras. She began bringing a gym bag packed with bottles for urine, trash bags, and a change of clothes in case of accidents. “It kind of felt like you were loading up to go to war just to deliver some packages,” she said. She reported that routinely delaying bathroom breaks led to kidney issues and yeast infections, health problems she says still affect her in her current job at a nursing home.

In May 2023, Cross filed a sex‑based discrimination charge with the Colorado Civil Rights Division, which processes workplace complaints under state law and also on behalf of the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). She alleged that Amazon’s delivery quotas and resulting lack of bathroom access had a disparate impact on women and other people with vaginas, in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Her claim was later transferred to the EEOC’s Denver office, which began investigating in January 2024, according to legal summaries of her case. The Nation reports that by December 2024, an EEOC official told Cross the agency was “very interested” in moving forward with her charge.

The legal theory at the heart of her complaint—known as disparate impact—focuses on the effects of a policy rather than an employer’s intent. Under Title VII and subsequent case law, neutral rules can be unlawful if they disproportionately harm protected groups and are not job‑related or necessary.

That framework came under direct challenge after Trump returned to the White House. In April 2025, Trump issued Executive Order 14281, titled “Restoring Equality of Opportunity and Meritocracy,” instructing federal agencies to deprioritize enforcement actions based on disparate impact theories of liability. The order followed calls from the conservative Project 2025 policy blueprint to eliminate disparate impact across the federal government.

In May 2025, Thomas Colclough, the EEOC’s director of the Office of Field Programs, circulated a memo to state and local partners saying the commission would no longer pay them to process disparate impact claims on its behalf and warning that such cases would be subject to “substantial weight review,” The Nation reports. Agencies that repeatedly issued decisions at odds with the EEOC’s approach risked losing their federal certification and funding.

The policy hardening continued. In June 2025, the EEOC withdrew from a racial discrimination lawsuit it had filed in April 2024 against the Sheetz convenience store chain, a case that alleged the company’s criminal background check practices disproportionately harmed Black, Native American and multiracial job applicants. The Nation notes that the lawsuit, brought on behalf of applicants including Pennsylvania worker Kenni Miller, had already produced findings of reasonable cause to believe discrimination occurred. After the agency stepped back, Miller moved to intervene so he could try to continue the case privately, saying in a statement that “the government is abandoning our case.”

Then in September 2025, EEOC Chair Andrea Lucas issued an internal memorandum instructing staff to administratively close all pending disparate impact charges under Title VII and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act, The Nation reports. Two EEOC employees with knowledge of the change told the magazine that the agency has since stopped moving forward on such charges or bringing new disparate impact litigation.

One consequence of that directive was the closure of Cross’s case. According to Cross and court filings described by outlets including The Nation, the Associated Press and Reuters, the EEOC notified her on September 29, 2025, that it was closing her charge shortly after adopting the new policy. Officials did not cite the merits of her allegations, she and her lawyers say, but instead relied on the commission’s decision to halt disparate impact investigations following Trump’s executive order.

Civil rights lawyers and former officials argue the commission’s retreat conflicts with federal law. Jenny Yang, a former EEOC chair now in private practice, and attorney Joseph Sellers told The Nation that the Supreme Court has long recognized disparate impact as a valid theory under Title VII, beginning with a 1971 decision, and that Congress codified disparate impact protections in the Civil Rights Act of 1991. “This is clearly established law,” Sellers said, adding that abandoning it is likely unlawful because the agency is required by statute to investigate discrimination charges.

With federal enforcement curtailed, workers still technically may bring private lawsuits based on disparate impact theories. But legal experts interviewed by The Nation say those cases are often difficult and expensive to pursue without the EEOC’s investigative tools, access to employer data, and ability to bring cases on workers’ behalf.

In October 2025, Cross responded by suing the EEOC in federal court in Washington, D.C., arguing that the commission’s new policy and the closure of her charge violated Title VII, the Age Discrimination in Employment Act and the Administrative Procedure Act. Her suit, supported by public‑interest legal groups, asked the court to block the policy, order the EEOC to reopen her investigation and require the agency to disclose all disparate impact charges it had closed.

On November 25, 2025, U.S. District Judge Trevor McFadden dismissed Cross’s lawsuit, ruling that she lacked standing to challenge the agency’s enforcement priorities, according to Reuters and legal analyses of the decision. McFadden did not address the underlying legality of the EEOC’s disparate‑impact policy, instead holding that federal courts are not the proper forum to direct how the executive branch allocates investigative resources.

Cross has said the dismissal was devastating after years of trying to challenge the conditions she described at Amazon. She told The Nation that having the agency first signal interest in her case and then abandon it left her feeling that her experience “didn’t matter.” Her legal team has indicated it is weighing next steps, including a possible appeal, in hopes of restoring the EEOC’s role in investigating allegations like hers.