Scientists at the University of California, Riverside have identified a previously unknown form of mitochondrial DNA damage known as glutathionylated DNA adducts, which build up at dramatically higher levels in mitochondrial DNA than in nuclear DNA. The lesions disrupt energy production and activate stress-response pathways, and researchers say the work could help explain how damaged mitochondrial DNA contributes to inflammation and diseases including diabetes, cancer and neurodegeneration.

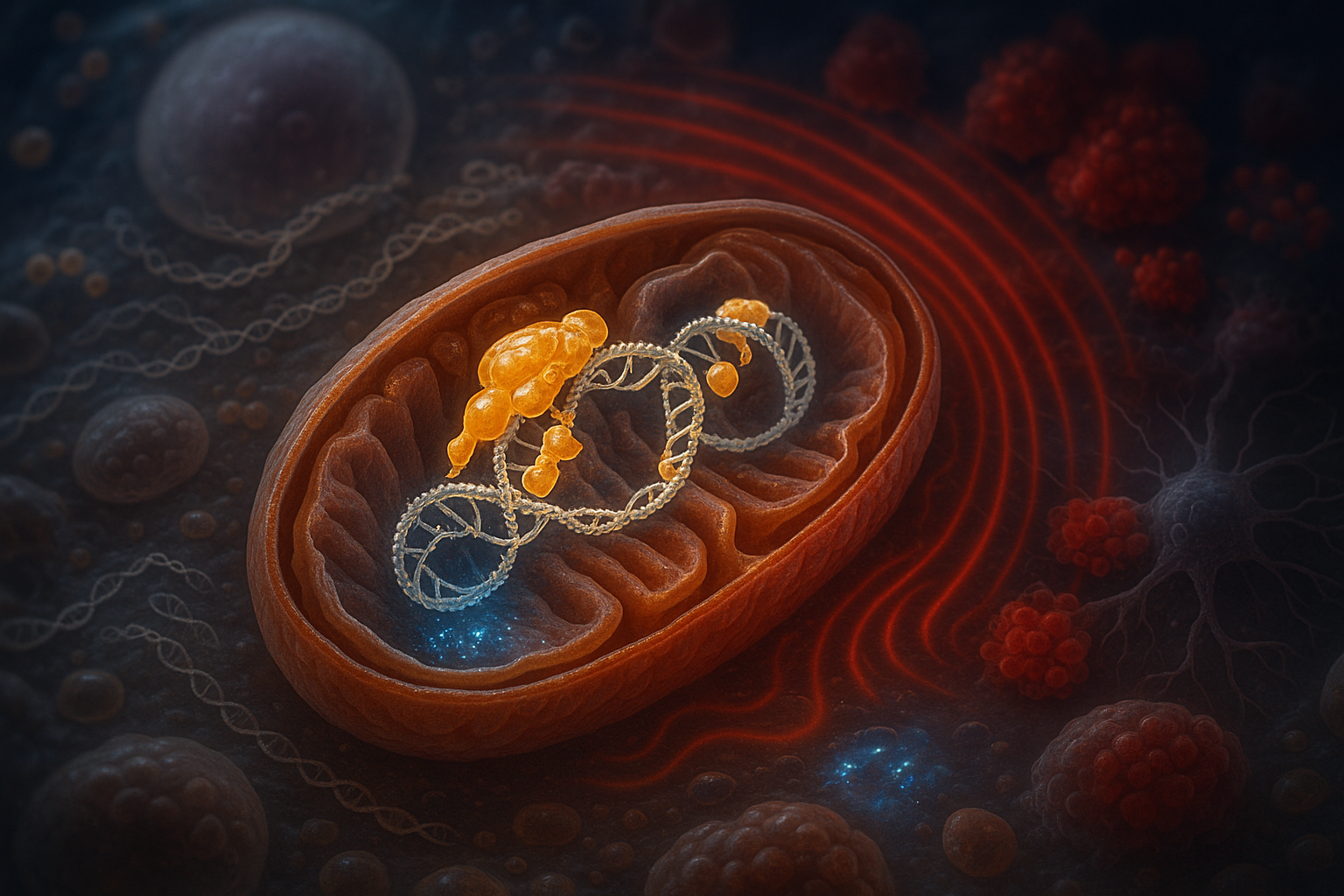

Mitochondria, the cell's energy producers, contain their own genetic material known as mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which accounts for roughly 1–5% of a cell's total DNA. Unlike nuclear DNA (nDNA), mtDNA is circular, carries 37 genes, and is inherited exclusively from the mother, while nDNA is linear and passed down from both parents.

Scientists have long known that mtDNA is prone to damage, but the biological details have been unclear. A UC Riverside-led study now pinpoints a specific culprit: glutathionylated DNA (GSH-DNA) adducts, a newly identified, "sticky" form of DNA damage that forms when a chemical group attaches directly to the DNA.

In experiments using cultured human cells, the research team found that these bulky chemical attachments accumulate in mtDNA at levels up to 80 times higher than in nuclear DNA, underscoring mtDNA's particular vulnerability to this type of injury. The work was led by Linlin Zhao, an associate professor of chemistry at UC Riverside, and is described in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"mtDNA is more prone to damage than nDNA," Zhao said in a UC Riverside news release. "Each mitochondrion has many copies of mtDNA, which provides some backup protection. The repair systems for mtDNA are not as strong or efficient as those for nuclear DNA."

The team linked the buildup of GSH-DNA adducts to marked changes in mitochondrial function. As the sticky lesions accumulate, proteins required for energy production decline, while proteins involved in stress responses and mitochondrial repair increase, indicating that cells attempt to counteract the damage.

The researchers also used advanced computer simulations to probe how the adducts alter the physical properties of mtDNA. The models suggested that the added chemical tags make the mitochondrial genome less flexible and more rigid, a change that may help mark damaged DNA for disposal so it is not copied and passed on.

Yu Hsuan Chen, the study's first author and a doctoral student in Zhao's laboratory, compared the problem to a damaged instruction manual inside an engine.

"When the engine's manual — the mtDNA — gets damaged, it's not always by a spelling mistake, a mutation," Chen said. "Sometimes, it's more like a sticky note that gets stuck to the pages, making it hard to read and use. That's what these GSH-DNA adducts are doing."

According to Zhao, the discovery of GSH-DNA adducts offers a new way to investigate how damaged mtDNA can act as a stress signal inside the body and potentially contribute to disease.

"Problems with mitochondria and inflammation linked to damaged mtDNA have been connected to diseases such as neurodegeneration and diabetes," Zhao said. "When mtDNA is damaged, it can escape from the mitochondria and trigger immune and inflammatory responses. The new type of mtDNA modification we've discovered could open new research directions to understand how it influences immune activity and inflammation."

The study, which also has implications for conditions such as cancer that are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, was carried out by researchers at UC Riverside and the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. It was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and UC Riverside.

The findings appear in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in a paper titled "Glutathionylated DNA adducts accumulate in mitochondrial DNA and are regulated by AP endonuclease 1 and tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1."