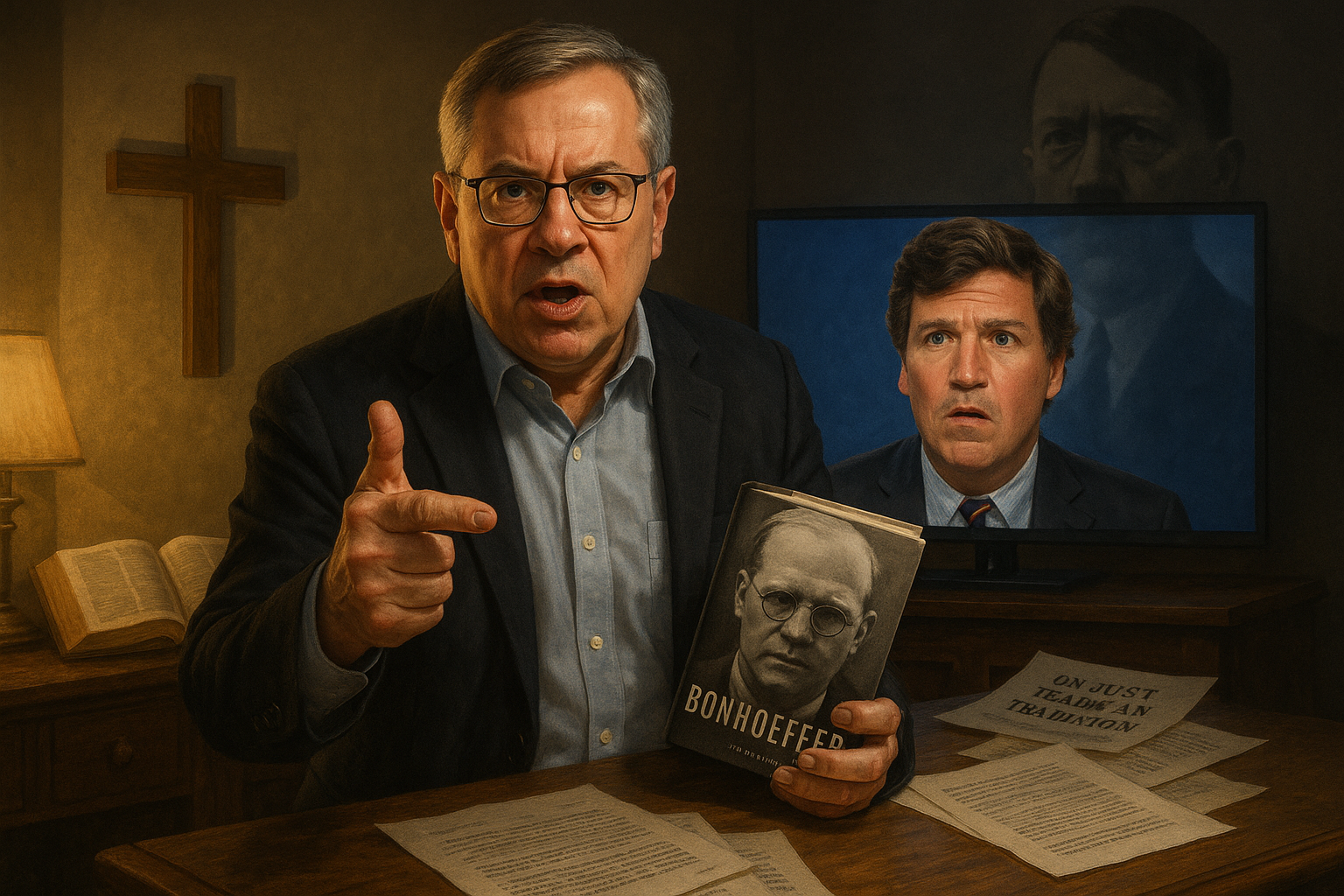

Tucker Carlson recently suggested that Dietrich Bonhoeffer set aside Christian ethics to support killing Adolf Hitler — a claim that commentator John Zmirak calls a misreading of both Bonhoeffer and Christian teaching. Zmirak argues Bonhoeffer’s resistance fits within the Christian just war tradition and warns against equating that context with today’s political rhetoric.

Tucker Carlson’s latest show drew sharp criticism after he said that when people are labeled “Nazis,” “we really have no choice but to start shooting them,” invoking Dietrich Bonhoeffer as someone who, in Carlson’s words, concluded that “Christianity is not enough, we have to kill the guy.” Multiple outlets transcribed the remarks from his episode criticizing commentators Mark Levin and Ben Shapiro.

Writing in The Daily Wire, John Zmirak argues Carlson mischaracterized both Bonhoeffer and Christianity. He contends historic Christian thought is not strictly pacifist and that Bonhoeffer’s resistance to the Nazi dictatorship aligns with the just war tradition rather than a rejection of faith.

What Bonhoeffer did — and did not — do is well documented. He was a Lutheran pastor tied to the Confessing Church, joined circles of German resistance, was linked to plots against Hitler (including the July 20, 1944 conspiracy), and was executed by hanging at Flossenbürg on April 9, 1945. Biographies and major reference works describe him as aware of and morally supportive of efforts to remove Hitler, without evidence he personally attempted an assassination.

Zmirak frames his case inside mainstream just war teaching, long articulated in Christian theology and summarized in the Catholic Catechism: force may be used only under strict conditions — grave and certain harm by an aggressor, exhaustion of other means, serious prospects of success, and that force not create greater evils. He also notes that Reformation‑era resistance theorists in both Jesuit and Calvinist traditions developed arguments for opposing tyrants; scholars often cite Juan de Mariana among Jesuits and the Huguenot tract Vindiciae contra tyrannos among Reformed writers as emblematic of that line of thought. Those strands helped inform later debates over justified rebellion, distinct from violence in constitutional democracies.

To contextualize Bonhoeffer’s choices, Zmirak contrasts Nazi rule with present‑day politics. The historical record shows the regime seized extraordinary powers during crisis, suspended civil liberties after the Reichstag Fire (February 1933), enabled rule by decree (the Enabling Act, March 1933), outlawed opposition parties (July 1933), and stripped Jews of citizenship under the Nuremberg Laws (1935). The dictatorship built a vast system of camps and pursued conquest and extermination in Eastern Europe; scholars describe Generalplan Ost and related policies as envisioning the removal and mass death of tens of millions through starvation, deportation, enslavement, and murder. Against that backdrop, Bonhoeffer and fellow conspirators believed tyrannicide in wartime could be morally defensible.

Zmirak also cautions against casually branding opponents “Nazis” or “fascists” today. He points to recent online exchanges in which California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s press office labeled White House deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller a “fascist.” Separately, reporting this fall detailed incidents in which an activist posted flyers in Miller’s Virginia neighborhood listing his home address — a doxxing case now at the center of a legal dispute. Those episodes, Zmirak argues, illustrate how incendiary language can escalate tensions, though the doxxing itself arose from a separate activist campaign, not from the governor’s post.

Zmirak closes by recommending Eric Metaxas’s biography of Bonhoeffer and a recent biopic as entry points for readers. Regardless of one’s view of those works, the core historical points are not in dispute: Bonhoeffer resisted a murderous dictatorship, wrestled deeply with Christian ethics, and was executed in April 1945 for his role in the resistance.