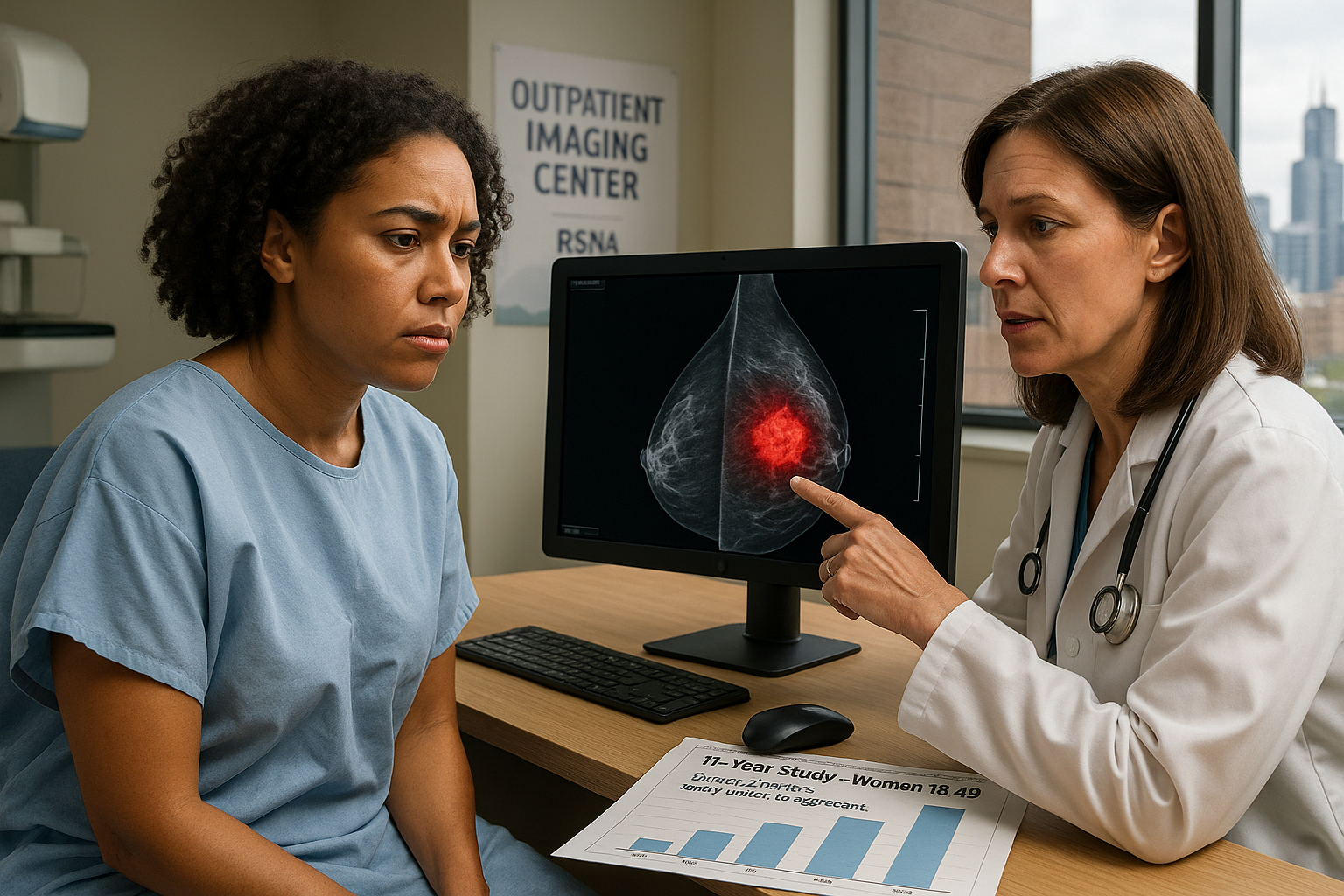

An 11-year review of breast cancer diagnoses from outpatient imaging centers in western New York found that women aged 18 to 49 accounted for roughly one-fifth to one-quarter of all cases, with many tumors in those under 40 described as invasive and biologically aggressive. The findings, presented at the Radiological Society of North America meeting, underscore calls for earlier, risk-based assessment for younger women.

An analysis of breast cancer diagnoses from seven outpatient centers in western New York over an 11‑year period found that 20% to 24% of all breast cancers occurred in women ages 18 to 49, according to research presented by the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) and reported by ScienceDaily. The review covered cases from 2014 through 2024 and focused on younger adults treated across a 200‑mile region.

Researchers led by radiologist Stamatia Destounis, M.D., of Elizabeth Wende Breast Care in Rochester, New York, identified 1,799 breast cancers in 1,290 women between 18 and 49 years old. Each year, the number of cancers in this age group ranged from 145 to 196. The average age at diagnosis was 42.6, with patients ranging from 23 to 49 years old.

The team collected details on how each cancer was detected, tumor type and other biological features, excluding cases that were not primary breast cancer. Of the 1,799 cancers, 731 (41%) were found on screening exams, while 1,068 (59%) were detected through diagnostic evaluations prompted by symptoms or abnormal findings, ScienceDaily reports.

Most tumors in this younger group were invasive. The analysis found that 1,451 cancers (80.7%) were invasive and 347 (19.3%) were non‑invasive. Destounis noted that many of the invasive cancers, particularly in women under 40, were biologically aggressive, including some that were classified as triple‑negative — a subtype that does not respond to common hormone‑based therapies and is generally harder to treat.

"Most of these cancers were invasive, meaning they could spread beyond the breast, and many were aggressive types -- especially in women under 40," Destounis said in remarks released by RSNA. "Some were 'triple‑negative,' a form of breast cancer that is harder to treat because it doesn't respond to common hormone‑based therapies."

Although women under 50 accounted for only about 21% to 25% of those screened each year at the centers, they represented roughly one out of every four breast cancers diagnosed annually. Destounis described this as evidence that younger women bear a stable and substantial share of the breast cancer burden, and that their tumors are often more aggressive than guidelines may assume.

For women at average risk, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends mammography every other year from ages 40 to 74, while the American Cancer Society advises annual mammograms beginning at age 45, with the option to start at 40. Women considered high risk may be advised to undergo yearly breast MRI in addition to mammography starting around age 30. There are still no established screening recommendations for women younger than 30.

"This research shows that a significant proportion of cancers are diagnosed in women under 40, a group for whom there are no screening guidelines at this time," Destounis said. She and her colleagues argue that clinicians should perform risk assessments that factor in family history, genetic mutations, and certain racial and ethnic backgrounds to identify younger women who might benefit from more intensive or earlier screening.

The number of cancers diagnosed in younger women remained consistently high over the 11‑year period, even when fewer young women were seen overall, the RSNA report notes. Destounis said the steady case counts suggest that the issue will persist and should be addressed on a broader scale, with more emphasis on awareness, early risk evaluation and tailored screening approaches for women under 50, especially those under 40.