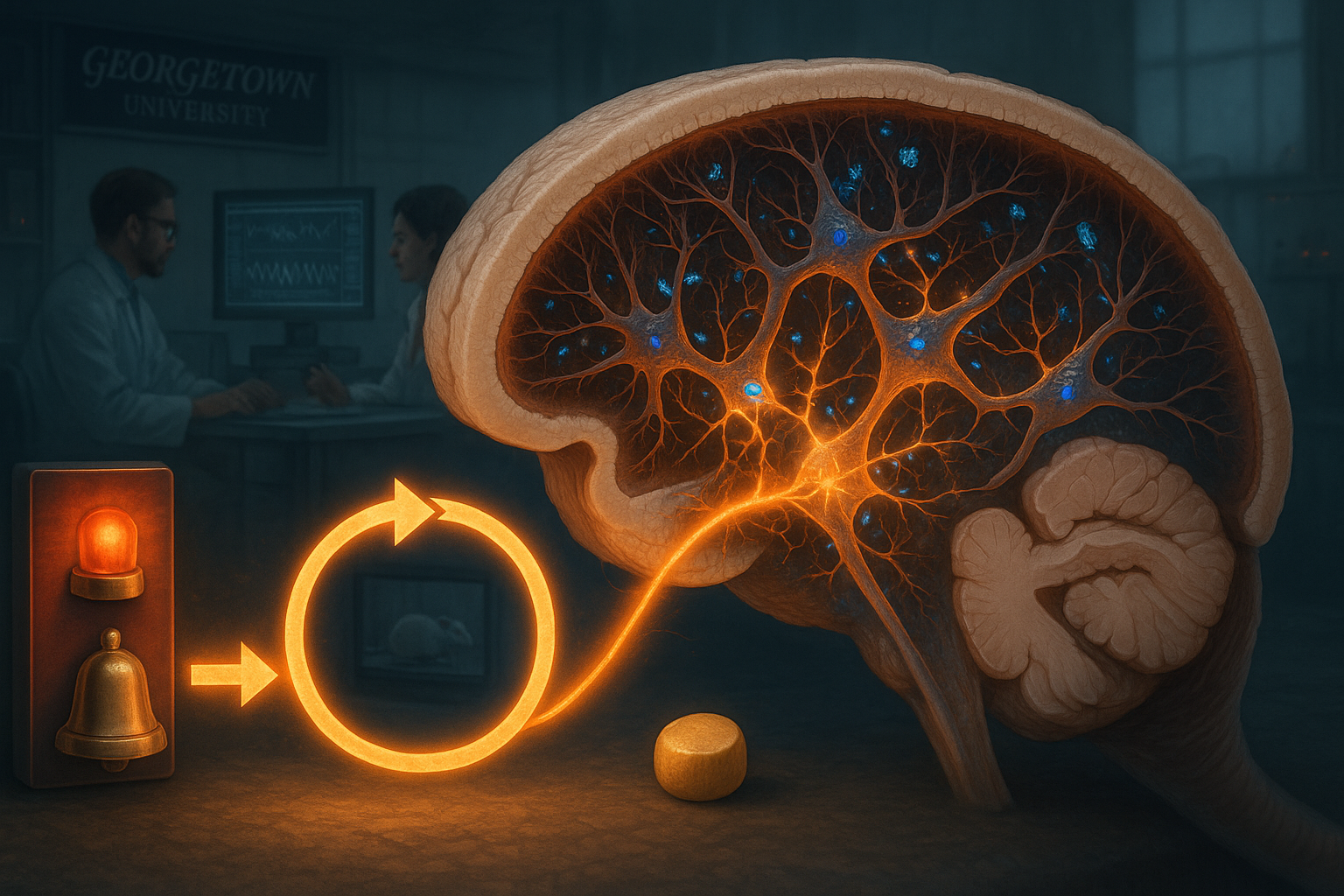

Researchers at Georgetown University Medical Center report that shifts in the brain protein KCC2 can change how strongly everyday cues become linked to rewards. In a study published December 9 in Nature Communications, they show that reduced KCC2 activity in rats is associated with intensified dopamine neuron firing and stronger cue–reward learning, offering clues to mechanisms that may also be involved in addiction and other psychiatric disorders.

A team led by Alexey Ostroumov, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Pharmacology & Physiology at Georgetown University School of Medicine, examined how the brain links cues to rewarding outcomes.

The work focuses on KCC2, a potassium–chloride cotransporter that helps regulate chloride levels inside neurons and thereby influences how inhibitory signals shape neural circuit activity.

According to materials from Georgetown University Medical Center and the Nature Communications paper, the investigators found that changes in the learning process can occur when KCC2 levels shift. In an inverse relationship, diminished KCC2 function in midbrain inhibitory neurons was associated with increased firing and synchronization in circuits that influence dopamine neurons, leading to stronger reward-related responses and the formation of new cue–reward associations in rats.

To probe these mechanisms, the researchers combined studies of rodent brain tissue with classic Pavlovian cue–reward experiments in rats. In these behavioral tests, a brief sound signaled that a sugar cube was about to be delivered, allowing the team to monitor how neural activity changed as the animals learned to associate the cue with the reward.

Beyond the overall pace of neuron firing, the study found that when neurons act in a coordinated pattern, they can amplify dopamine activity. Brief, synchronized bursts from these circuits were linked to stronger dopamine responses to rewards and reward-predicting cues, which the authors interpret as potent learning signals that help the brain assign value to particular experiences.

"Our ability to link certain cues or stimuli with positive or rewarding experiences is a basic brain process, and it is disrupted in many conditions such as addiction, depression, and schizophrenia," Ostroumov said, according to a Georgetown news release. He noted that prior work suggests drug abuse can alter KCC2, potentially allowing addictive substances to interfere with normal learning processes.

The researchers also explored how drugs acting on specific receptors, including the benzodiazepine diazepam, influence the coordination of neuronal firing. Earlier experiments from the group indicated that changes in KCC2 production, and the resulting shifts in neuronal activity, can alter how diazepam produces its calming effects. The new study builds on that work by showing that, during learning, changes in KCC2-dependent chloride balance in midbrain inhibitory networks can reshape how dopamine circuits respond to cues and rewards.

To reach their conclusions, the team used a combination of electrophysiology, pharmacology, fiber photometry, behavioral testing, computational modeling and molecular analyses. First author Joyce Woo, a PhD candidate in Ostroumov's lab, noted in Georgetown's coverage of the research that while many neuroscience experiments use mice, the group relied on rats for the behavioral components because rats tend to perform more reliably on longer or more complex reward-learning tasks, yielding more stable data.

"Our findings help explain why powerful and unwanted associations form so easily, like when a smoker who always pairs morning coffee with a cigarette later finds that just drinking coffee triggers a strong craving to smoke," Ostroumov said in a press statement. He added that preventing maladaptive cue–drug associations or restoring healthier patterns of neural communication could help in developing better treatments for addiction and related disorders.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, including MH125996 and DA048134, as well as NS139517 and DA061493, and by the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, the Whitehall Foundation and the Brain Research Foundation. In addition to Woo and Ostroumov, contributors included Ajay Uprety, Daniel J. Reid, Irene Chang, Aelon Ketema Samuel, Helena de Carvalho Schuch and Caroline C. Swain. The authors reported no personal financial interests related to the study.