Researchers at Case Western Reserve University report they have identified an abnormal interaction between the Parkinson’s-linked protein alpha-synuclein and the enzyme ClpP that disrupts mitochondrial function in experimental models. They also describe an experimental compound, CS2, designed to block that interaction, which they say improved movement and cognitive performance and reduced brain inflammation in lab and mouse studies.

Parkinson’s disease affects about 1 million people in the United States, with nearly 90,000 new diagnoses each year, according to the Parkinson’s Foundation.

Researchers at Case Western Reserve University say they have identified a molecular interaction that could help explain how Parkinson’s disease damages neurons. In a study published in Molecular Neurodegeneration, the team reports that alpha-synuclein—a protein known to accumulate in Parkinson’s disease—can bind abnormally to an enzyme called ClpP.

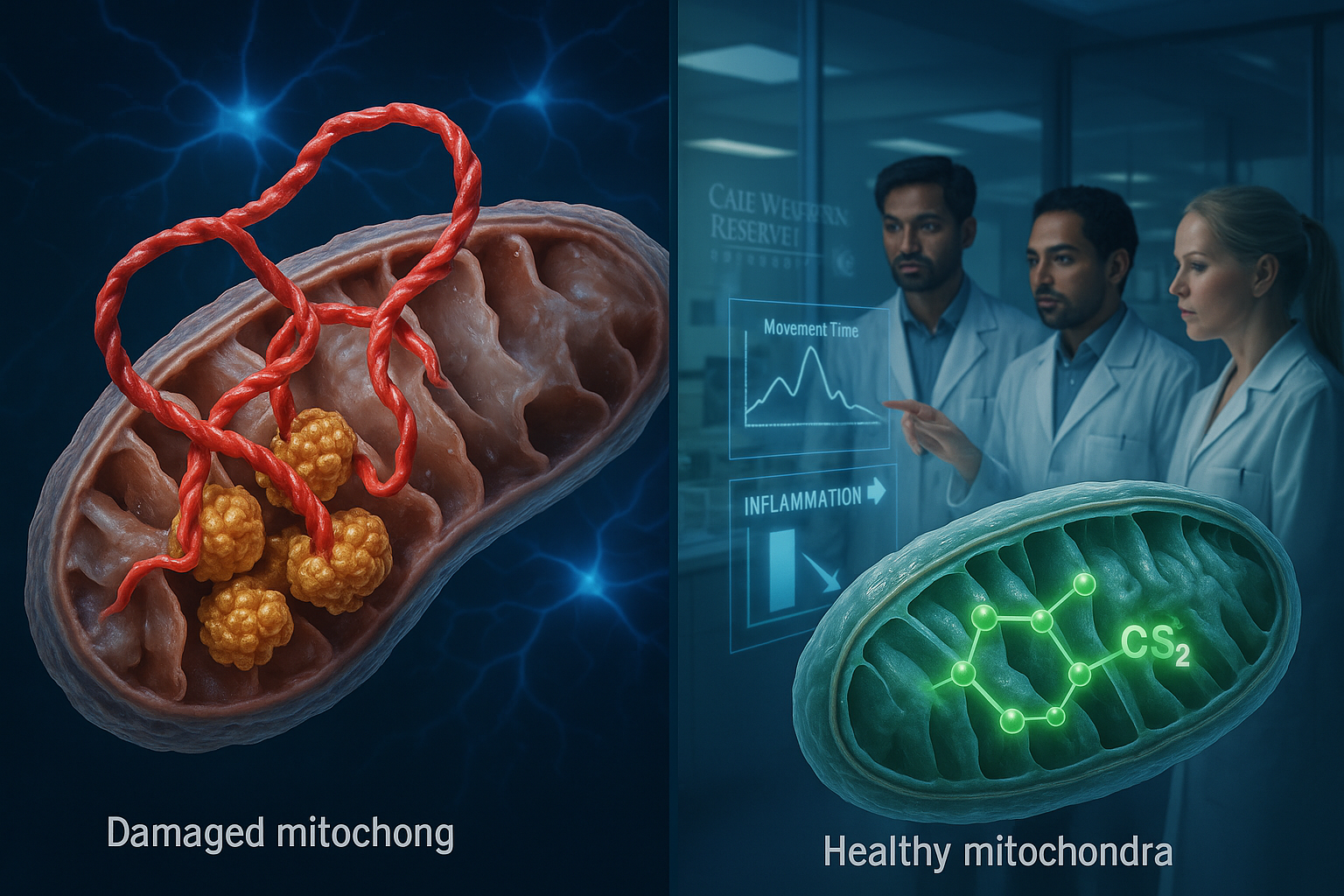

According to the researchers, ClpP normally helps maintain cellular health, but the abnormal binding interferes with its function and contributes to mitochondrial failure. Mitochondria are the cell’s energy-producing structures, and the study says their impairment can trigger neurodegeneration and brain cell loss. The researchers also reported that this interaction sped up Parkinson’s progression across several experimental models.

"We've uncovered a harmful interaction between proteins that damages the brain's cellular powerhouses, called mitochondria," said Xin Qi, the study’s senior author and the Jeanette M. and Joseph S. Silber Professor of Brain Sciences at the Case Western Reserve School of Medicine. "More importantly, we've developed a targeted approach that can block this interaction and restore healthy brain cell function."

To counter the effect, the researchers developed an experimental treatment called CS2, which they describe as a decoy designed to draw alpha-synuclein away from ClpP and prevent damage to the cell’s energy systems.

In tests across multiple models—including human brain tissue, patient-derived neurons and mouse models—the team reported that CS2 reduced brain inflammation and was associated with improvements in movement and cognitive performance.

"This represents a fundamentally new approach to treating Parkinson's disease," said Di Hu, a research scientist in the School of Medicine’s Department of Physiology and Biophysics. "Instead of just treating the symptoms, we're targeting one of the root causes of the disease itself."

The team said its next steps include refining CS2 for potential use in people, expanding safety and effectiveness testing, and identifying molecular biomarkers tied to disease progression, with the longer-term goal of moving toward human clinical trials.