Researchers at the University of California San Diego report that certain cancer cells survive targeted therapies by using low-level activation of a cell-death–linked enzyme, enabling them to endure treatment and later regrow tumors. Because this resistance mechanism does not depend on new genetic mutations, it appears early in treatment and may offer a new target to help prevent tumor relapse.

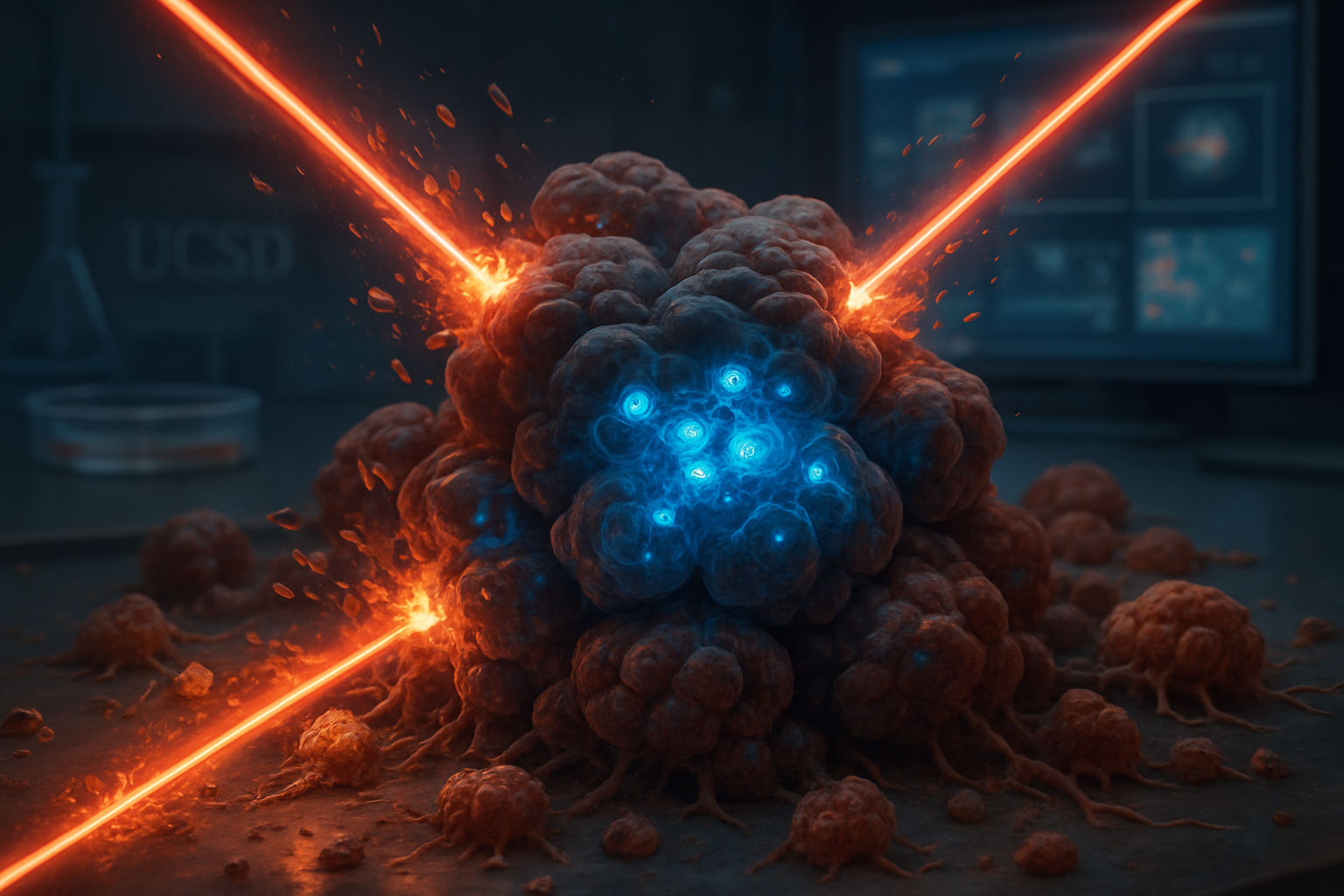

Cancer drug resistance is a major obstacle in oncology, as tumors often respond initially to treatment but later recur. Researchers at the University of California San Diego (UC San Diego) have now described an unexpected survival strategy in which cancer cells co-opt an enzyme usually active during cell death to withstand therapy and eventually regrow.

"This flips our understanding of cancer cell death on its head," said senior author Matthew J. Hangauer, Ph.D., assistant professor of dermatology at UC San Diego School of Medicine and member of Moores Cancer Center, in a statement released by the university. "Cancer cells which survive initial drug treatment experience sublethal cell death signaling which, instead of killing the cell, actually helps the cancer regrow. If we block this death signaling within these surviving cells, we can potentially stop tumors from relapsing during therapy."[0]

Cancer is responsible for about one in six deaths worldwide, and many of these deaths are linked to tumors that initially respond to treatment but later become resistant and return.[0][3] Resistance typically develops over months to years through new genetic mutations, a process often compared to the way bacteria evolve resistance to antibiotics. These mutation-driven changes can be difficult to control with the limited number of available drug combinations.[0][3]

The newly reported mechanism, by contrast, operates at the earliest stages of resistance and does not rely on permanent genetic changes, according to UC San Diego and collaborating reports. Because it emerges so soon after therapy begins and is non-genetic, the process is seen as a promising new point of attack for future treatments.[0][3][4]

"Most research on resistance focuses on genetic mutations," said first author August F. Williams, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in the Hangauer lab at UC San Diego. "Our work shows that non-genetic regrowth mechanisms can come into play much earlier, and they may be targetable with drugs. This approach could help patients stay in remission longer and reduce the risk of recurrence."[0][3]

In studies using models of melanoma, lung cancer and breast cancer, the team found that a subset of so-called "persister" cells that survive targeted treatment show chronic, low-level activation of DNA fragmentation factor B (DFFB), a protein that normally helps dismantle DNA during programmed cell death. The level of DFFB activation in these cells was too low to kill them but high enough to disrupt how they respond to growth-suppressing signals, allowing them to later resume proliferation.[0][3][4][6]

When researchers removed or suppressed DFFB in these persister cells, the cells remained dormant and did not regrow during drug treatment in experimental models. At the same time, DFFB was found to be nonessential in normal cells but required for the regrowth of cancer persister cells, suggesting that it could be a selective target for combination therapies aimed at extending responses to targeted drugs.[0][3][4][8]

The study, led by Williams and colleagues, reports that targeted therapy induces a growth-arrest mechanism in residual cancer persister cells through upregulation of type I interferon signaling, which is negatively regulated by the apoptotic DNA endonuclease DFFB. This regulation enables tumor relapse once treatment pressure is sustained or modified.[6]

The findings were published in 2025 in the journal Nature Cell Biology under the title "DNA fragmentation factor B suppresses interferon to enable cancer persister cell regrowth."[0][3][4][6] According to UC San Diego, the work was supported in part by grants from the U.S. Department of Defense, the National Institutes of Health and the American Cancer Society. Hangauer is a cofounder, consultant and research funding recipient of Ferro Therapeutics, a subsidiary of BridgeBio.[0][4][8]

While the results are based on preclinical models, the authors and independent commentators note that targeting DFFB or related pathways could eventually form the basis of new combination strategies designed to keep tumors dormant for longer and reduce the likelihood of relapse after targeted therapy.