Preclinical research from McGill University indicates that peripheral nerve injuries can cause long-term changes in the immune system across the body, with distinct patterns in male and female mice. Male mice showed strong and persistent inflammatory responses in the blood, while females did not show the same increase, yet serum from both sexes transmitted pain hypersensitivity when transferred to healthy mice. The findings point to previously unrecognized pathways involved in chronic pain and may open the door to more personalized treatments.

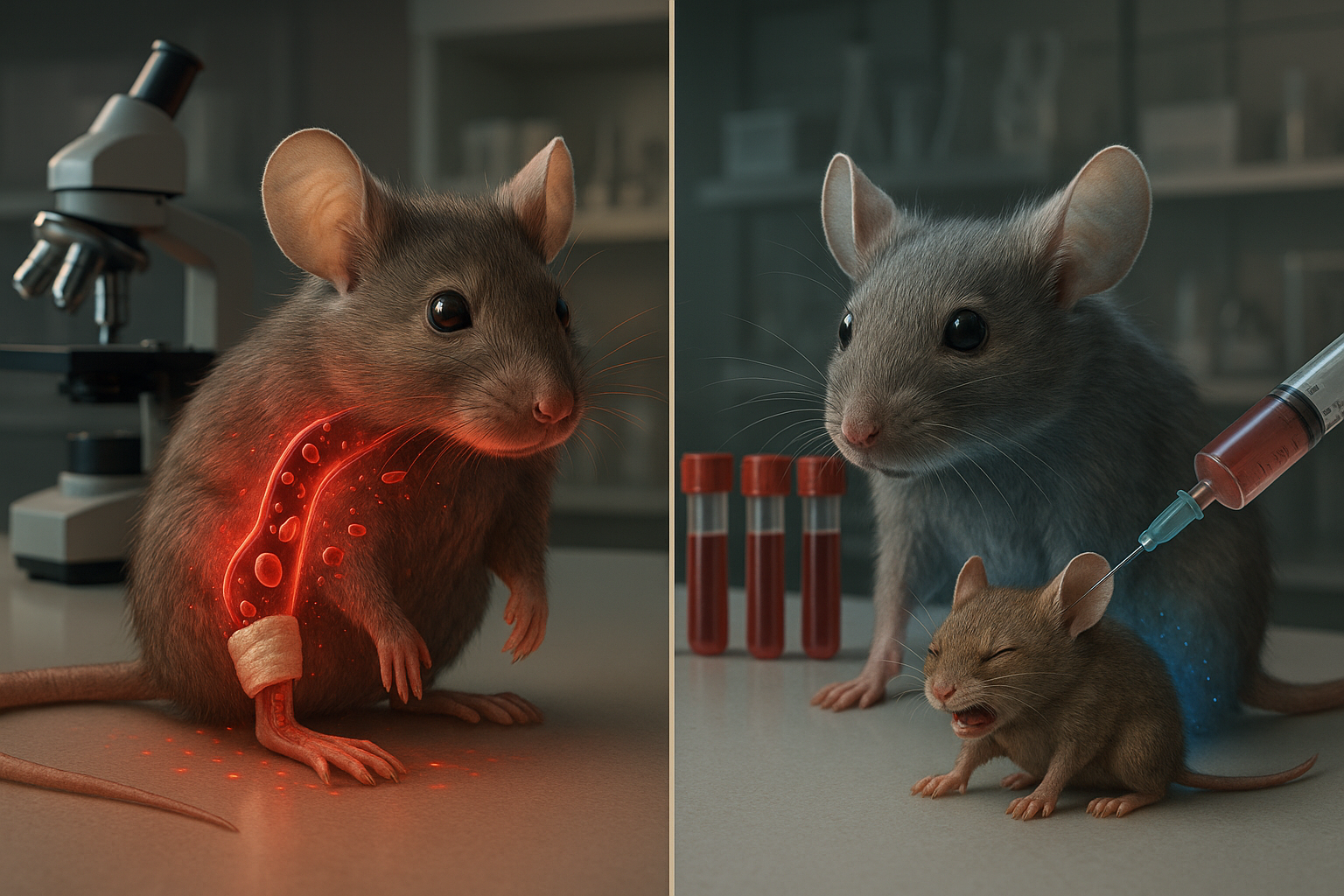

Nerve injuries, which can occur from stretching, pressure, or cuts, are common and often lead to chronic pain and other persistent complications. New preclinical work from McGill University suggests that such injuries do not just affect the damaged nerve but can also reshape immune activity throughout the entire body.

According to a report from McGill University published in Neurobiology of Pain, laboratory analysis of blood from mice showed clear signs of bodywide inflammatory changes after a peripheral nerve injury. Researchers used a spared nerve injury model in male and female mice and followed them for up to 20 months, repeatedly assessing pain sensitivity and immune-related factors in the blood.

The study found that, compared to sham surgery, male mice developed elevated levels of many inflammation-related proteins in their serum that remained dysregulated over time. In contrast, female mice showed a much more limited response, with far fewer inflammatory proteins consistently increased. Despite these differences, serum taken from both nerve-injured males and females induced heightened mechanical and cold pain sensitivity when transferred into otherwise healthy mice, regardless of whether the donor and recipient were the same sex.

"That means whatever is causing pain in females is working through a completely different biological pathway that we don't yet understand," said co-author Jeffrey Mogil, E.P. Taylor Professor of Pain Studies at McGill and a Distinguished James McGill Professor, in the McGill release.

The results suggest that factors circulating in the blood—differing between males and females—can propagate pain responses systemically. The authors note that injury-associated systemic inflammation may contribute to neuropathic pain, and that the underlying mechanisms appear to be sexually dimorphic.

"By understanding how men and women react differently to nerve injuries, we can work toward more personalized and effective treatments for chronic pain," said Sam Zhou, the study's lead author and a PhD student at McGill.

Beyond pain, the McGill team reports that long-lasting disruptions to immune function after nerve injury could potentially influence broader health risks. Their paper notes that persistent systemic inflammation following nerve damage might help explain links between chronic pain and conditions such as anxiety and depression, though this connection remains an area for further research rather than a proven causal pathway.

"Recognizing the full impact of nerve injuries is important for both doctors and patients," said senior author Dr. Ji Zhang, a professor in McGill's Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery and in the Faculty of Dental Medicine and Oral Health Sciences. "A localized nerve injury can affect whole body. Men and women may respond differently."

The study, titled "The impact of nerve injury on the immune system across the lifespan is sexually dimorphic," was published in Neurobiology of Pain (Volume 18, 2025). The research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Louise and Alan Edwards Foundation.