Stanford Medicine researchers have developed a combined blood stem cell and pancreatic islet cell transplant that, in mice, either prevents or cures type 1 diabetes using tissue from immunologically mismatched donors. The approach creates a hybrid immune system that halts autoimmune attacks without immunosuppressive drugs, and relies on tools already in clinical use, suggesting human trials may be feasible.

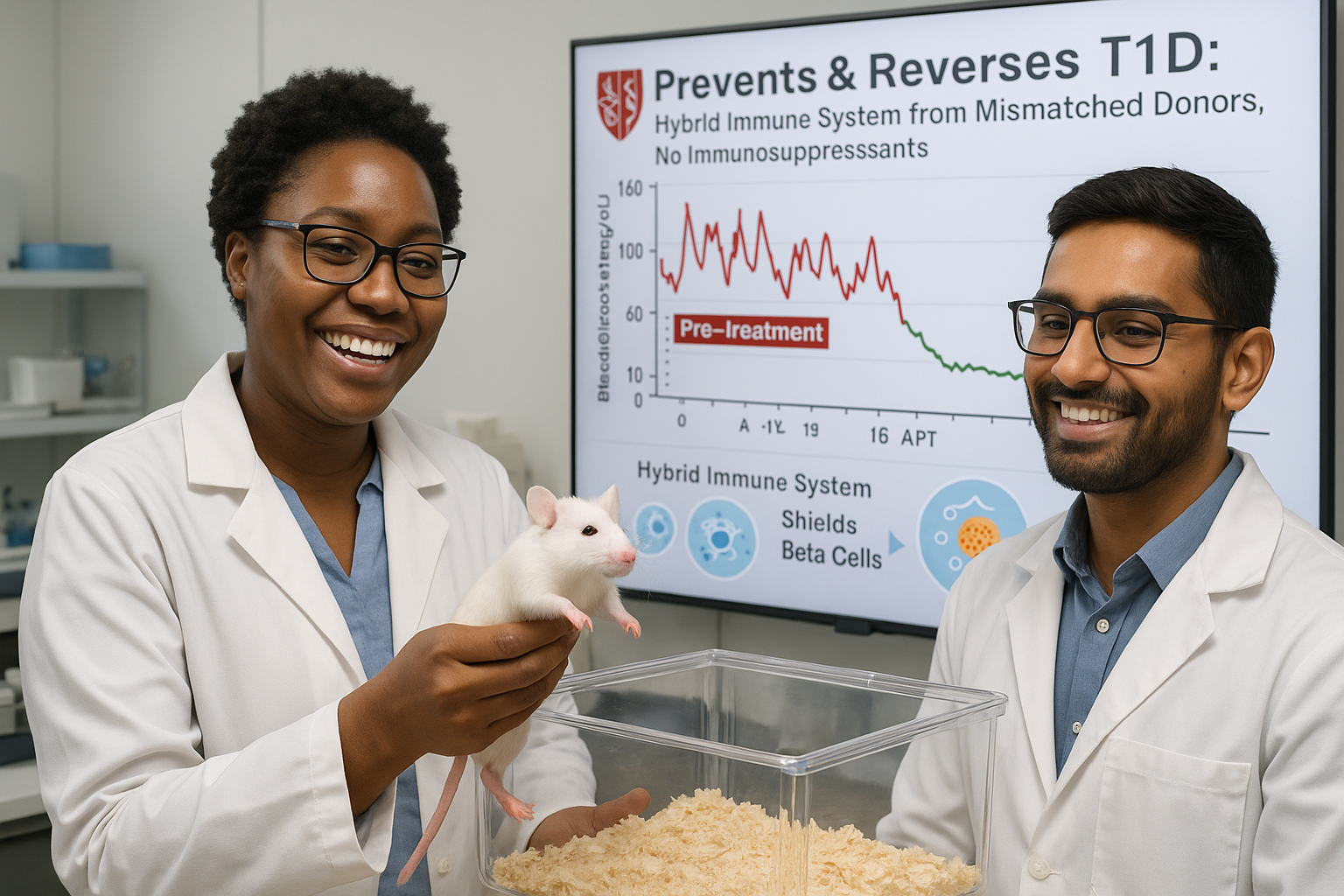

Scientists at Stanford Medicine report that a combined transplant of blood-forming stem cells and pancreatic islet cells from an immunologically mismatched donor either completely prevented or fully reversed type 1 diabetes in mice, according to a study published online November 18 in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

In type 1 diabetes, the immune system mistakenly attacks and destroys insulin-producing islet cells in the pancreas. The new method addresses this by establishing a hybrid immune system that includes cells from both the donor and the recipient. None of the treated mice developed graft-versus-host disease, in which donor-derived immune cells attack the host’s tissues, and the animals’ original immune systems stopped destroying islet cells. Throughout a six‑month study period, the mice required neither immunosuppressive drugs nor insulin injections.

"The possibility of translating these findings into humans is very exciting," said Seung K. Kim, MD, PhD, the KM Mulberry Professor and a professor of developmental biology, gerontology, endocrinology and metabolism at Stanford Medicine, and senior author of the study. Kim, who directs the Stanford Diabetes Research Center and the Northern California Breakthrough T1D Center of Excellence, added: "The key steps in our study—which result in animals with a hybrid immune system containing cells from both the donor and the recipient—are already being used in the clinic for other conditions."

Lead author Preksha Bhagchandani, a graduate and medical student, and colleagues built on a 2022 study from the same group in which they induced diabetes in mice by using toxins to destroy insulin-producing cells in the pancreas, then restored blood sugar control with a gentle pre‑transplant regimen of immune‑targeting antibodies and low‑dose radiation, followed by blood stem cell and islet cell transplants from an unrelated donor.

The new research tackled a more challenging model: spontaneous autoimmune diabetes, which more closely resembles human type 1 diabetes. In this setting, transplanted islet cells face rejection because they are foreign tissue and are also targeted by an immune system already primed to attack islet cells. To overcome this, Bhagchandani and co‑author Stephan Ramos, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow, added a commonly used autoimmune disease drug to the previously developed pre‑transplant regimen. According to Stanford’s account of the work, this adjusted protocol, followed by blood stem cell transplantation, generated a hybrid immune system and prevented type 1 diabetes in 19 out of 19 at‑risk mice. In a separate group of animals with long‑standing disease, nine out of nine were cured after receiving the combined blood stem cell and islet cell transplant.

This work extends earlier research led by the late Samuel Strober, MD, PhD, and his colleagues, including co‑author Judith Shizuru, MD, PhD, at Stanford Medicine. That research showed that a bone marrow transplant from a partially immunologically matched human donor could establish a hybrid immune system in the recipient and allow long‑term acceptance of a kidney transplant from the same donor, in some cases for decades, without ongoing immunosuppression.

Blood stem cell transplants are already used to treat cancers of the blood and immune system, such as leukemia and lymphoma, but conventional preparations often rely on high‑dose chemotherapy and radiation that can cause severe side effects. Shizuru and colleagues have developed a gentler conditioning strategy using antibodies, drugs and low‑dose radiation that reduces bone marrow activity enough to allow donor blood stem cells to engraft, potentially making the procedure suitable for noncancerous conditions such as type 1 diabetes.

Despite the promising mouse data, important challenges remain before this strategy could be widely used in people. For now, pancreatic islets are typically obtained only from deceased donors, and the blood stem cells must come from the same donor as the islets. It is also uncertain whether the number of islet cells recovered from one donor would always be sufficient to reverse established type 1 diabetes.

Researchers are exploring ways to address these limitations, including producing large quantities of islet cells in the laboratory from pluripotent human stem cells and improving the survival and function of transplanted islets. The team also believes that the gentle preconditioning and hybrid immune system approach could eventually be applied to other autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, to certain noncancerous blood disorders like sickle cell anemia, and to transplants involving immunologically mismatched solid organs.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Breakthrough T1D Northern California Center of Excellence, Stanford Bio‑X, the Reid Family, the H.L. Snyder Foundation and Elser Trust, the VPUE Research Fellowship at Stanford, the Stanford Diabetes Research Center, and other institutional and philanthropic sources, according to Stanford Medicine.