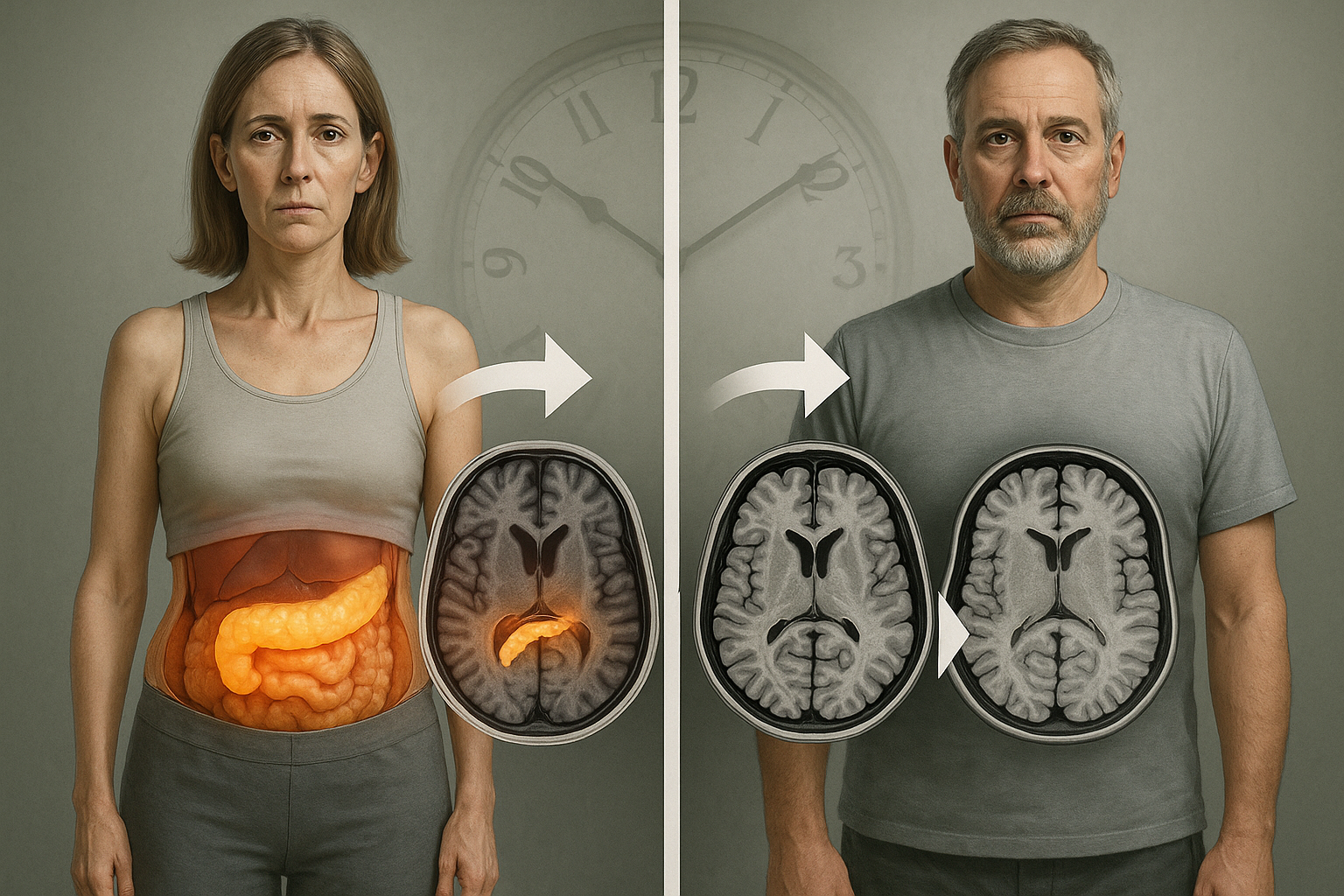

Where fat is stored in the body—not only how much—is linked to brain structure and cognition, according to a large MRI study of nearly 26,000 UK Biobank participants. Researchers reported that two fat distribution profiles—one marked by high pancreatic fat and another often described as “skinny fat,” with high fat relative to muscle despite a less-obese appearance—were associated with gray-matter loss, faster brain aging and poorer cognitive outcomes.

Obesity’s relationship with brain health may depend on more than total weight or body mass index (BMI), according to research published January 27, 2026 in Radiology, the flagship journal of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

Researchers at The Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University in Xuzhou, China analyzed MRI-based body composition measures alongside brain imaging and health information from 25,997 participants in the UK Biobank, a large research resource that pairs imaging with physical measurements, demographics, medical history, biomarkers and lifestyle data.

Using a data-driven approach, the team described two fat distribution profiles that showed the strongest associations with adverse brain and cognitive findings. The profiles were linked to more extensive gray-matter atrophy, accelerated brain aging, cognitive decline and higher risk of neurological disease, and the associations were observed in both men and women, with the researchers reporting nuanced sex-related differences.

High pancreatic fat, even without high liver fat

One profile—described as “pancreatic predominant”—was characterized by an unusually high concentration of fat in the pancreas. In this group, the pancreatic proton density fat fraction (an MRI measure used to estimate fat concentration in tissue) was around 30%, which coauthor Kai Liu, M.D., Ph.D., said is about two to three times higher than in other fat-distribution categories and can be up to six times higher than in lean individuals.

Liu, an associate professor in the hospital’s radiology department, said the pancreatic-predominant group also tended to have higher BMI and overall body fat, while liver fat was not significantly higher than in other profiles—an imaging pattern he said can be overlooked in routine practice.

“In our daily radiology practice, we often diagnose ‘fatty liver,’” Liu said. “But from the perspectives of brain structure, cognitive impairment and neurological disease risk, increased pancreatic fat should be recognized as a potentially higher-risk imaging phenotype than fatty liver.”

The “skinny fat” profile

The second profile—described by the researchers as “skinny fat”—showed a high fat burden in most body regions except the liver and pancreas. Unlike more evenly distributed obesity patterns, fat in this group tended to be more concentrated in the abdomen.

Liu said this profile does not necessarily match the common visual stereotype of severe obesity: its average BMI ranked fourth among the study’s fat-distribution categories. He emphasized that the distinguishing feature was a higher fat proportion relative to muscle.

“Most notably, this type does not fit the traditional image of a very obese person, as its actual average BMI ranks only fourth among all categories,” Liu said. “Therefore, if one feature best summarizes this profile, I think, it would be an elevated weight-to-muscle ratio, especially in male individuals.”

What the findings do—and do not—show

The study highlights MRI’s ability to quantify fat in specific organs and compartments, going beyond broad measures such as BMI. “Brain health is not just a matter of how much fat you have, but also where it goes,” Liu said.

The analysis focused on brain structure, cognition and neurologic disease risk. The researchers said additional studies are needed to clarify how these fat-distribution patterns might relate to other outcomes, including cardiovascular and metabolic health, and whether changing these patterns can reduce risk.