Researchers report that Enterococcus faecalis—a bacterium often found in chronic wounds—can hinder skin repair by generating hydrogen peroxide through a metabolic pathway, triggering stress responses that stop key skin cells from migrating. In laboratory experiments, breaking down the peroxide with the antioxidant enzyme catalase helped restore cell movement, suggesting a potential treatment approach that does not rely on antibiotics.

Chronic wounds are a growing health challenge and can lead to serious complications, including amputation. An international research team says it has identified a mechanism by which a common wound-associated bacterium, Enterococcus faecalis, can directly interfere with the body’s ability to repair damaged skin.

In a study published in Science Advances, the researchers—led by Associate Professor Guillaume Thibault of Nanyang Technological University (NTU) in Singapore and Professor Kimberly Kline of the University of Geneva—found that E. faecalis can impair wound closure not only by surviving treatment, but by producing reactive oxygen species as a byproduct of its metabolism.

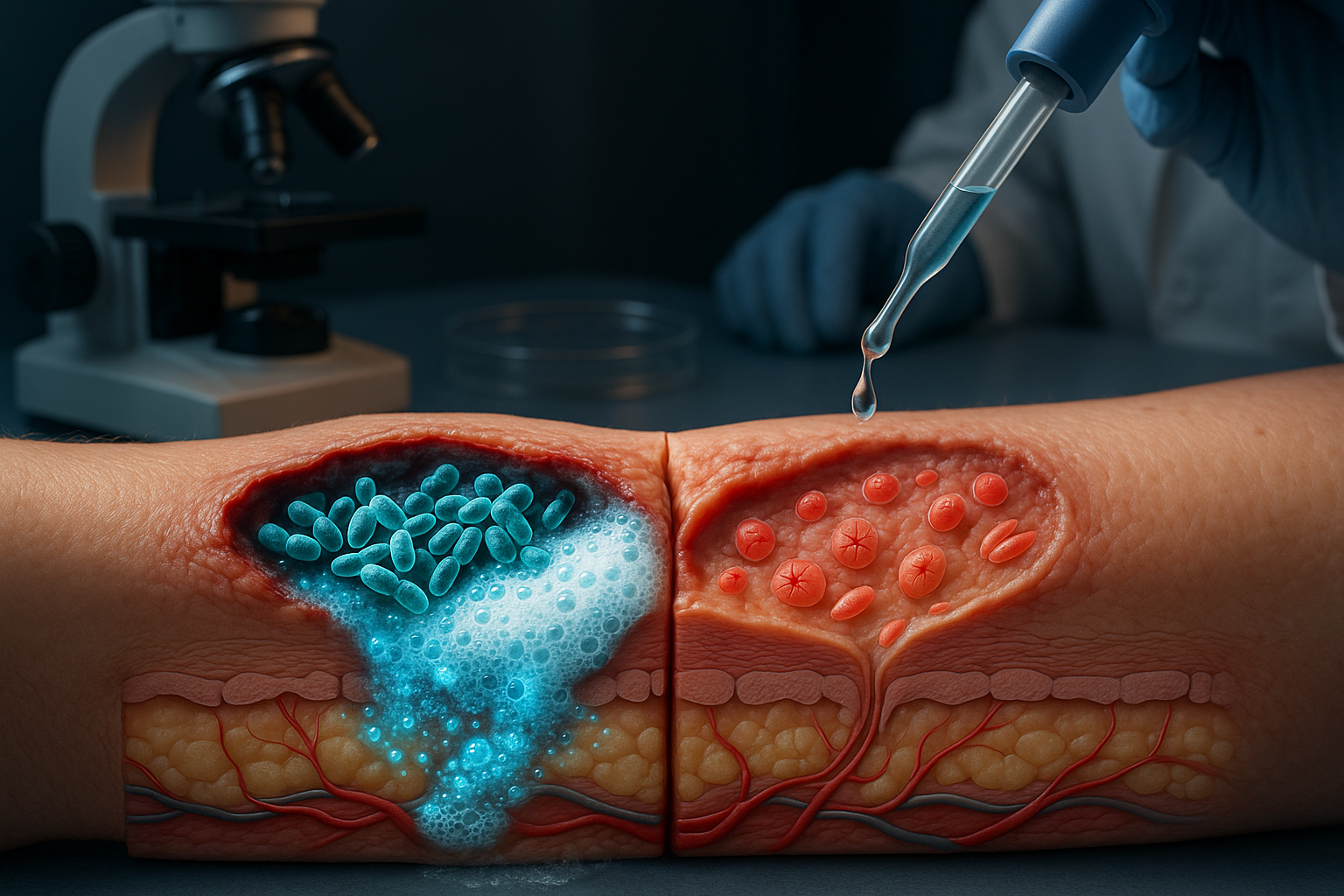

The team reports that E. faecalis uses a metabolic process known as extracellular electron transport (EET) that generates hydrogen peroxide. In lab experiments with human skin cells, hydrogen peroxide induced oxidative stress in keratinocytes, cells that help close wounds. That stress activated the unfolded protein response, a cellular pathway that can be protective but, in this setting, was linked to reduced keratinocyte migration—slowing the process needed to seal damaged tissue.

To test the role of EET, the researchers used a genetically modified E. faecalis strain lacking the EET pathway. Those bacteria produced substantially less hydrogen peroxide and were less able to block keratinocyte migration in laboratory assays, the study found.

The team also tested whether neutralizing hydrogen peroxide could reverse the effect. Treating skin cells with catalase—an antioxidant enzyme that breaks down hydrogen peroxide—reduced stress signaling and helped restore keratinocyte migration in lab experiments.

“Our findings show that the bacteria’s metabolism itself is the weapon, which was a surprise finding previously unknown to scientists,” Thibault said in NTU’s statement about the work.

The researchers said the results point to a treatment strategy that could complement or, in some cases, reduce reliance on antibiotics: targeting harmful bacterial byproducts rather than attempting to eliminate bacteria outright. They suggested that wound dressings infused with antioxidants such as catalase could be a practical avenue for further development.

The group said it is conducting studies in animal models to determine effective delivery methods before moving toward human clinical trials.