Researchers at The Rockefeller University have identified a molecular switch in breast cancer cells that helps them survive harsh conditions. The switch involves deacetylation of the MED1 protein, which boosts stress-response gene activity linked to tumor growth and resilience. The work, reported in Nature Chemical Biology, points to potential new targets for cancer therapy.

Cancer cells often flourish in hostile tumor environments, such as regions with low oxygen or high oxidative stress. Seeking to understand how breast cancer cells adapt, a team led by Robert Roeder at The Rockefeller University examined how changes in gene transcription enable tumor cells to cope with these conditions.

The researchers focused on the Mediator complex, a large protein assembly that helps RNA polymerase II (Pol II) transcribe genes. One key subunit, MED1, is required for Pol II-driven transcription in many cell types, including estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer (ER+ BC), one of the most common categories of breast cancer. Earlier work from Roeder’s lab showed that MED1 interacts with estrogen receptors to strongly activate gene expression in ER+ BC, and in some cases this interaction can reduce the effectiveness of cancer drugs, according to Rockefeller University and ScienceDaily summaries of the study.

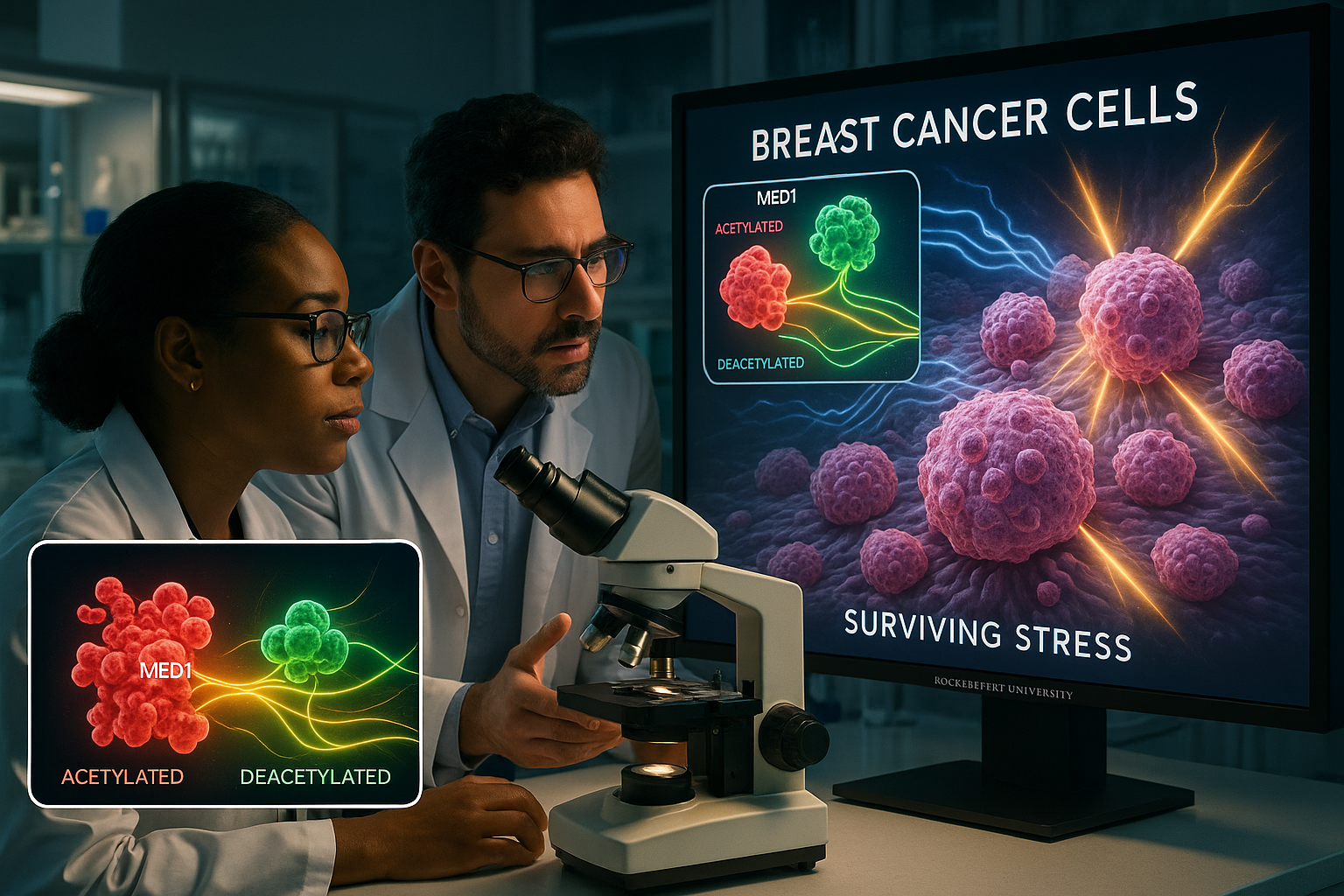

First author Ran Lin began by asking whether MED1 is modified by acetylation, a chemical change in which an acetyl group is added to a protein and its function can be altered. After confirming that MED1 is acetylated, the team exposed cells to several types of stress, including hypoxia (lack of oxygen), oxidative stress, and heat or thermal stress.

Under these stressful conditions, the enzyme SIRT1 removed acetyl groups from MED1 in a process known as deacetylation. The deacetylated MED1 then associated more efficiently with Pol II, increasing the potential to activate genes that help cells cope with damage and other stressors, the Rockefeller account reports.

To test this mechanism more directly, the researchers engineered a mutant form of MED1 lacking six specific acetylation sites, making it unable to be acetylated. They introduced this mutant protein into ER+ breast cancer cells in which the endogenous MED1 had been removed using CRISPR-based gene editing. In laboratory and animal models, breast cancer cells containing deacetylated or non-acetylatable MED1 formed faster-growing and more stress-resistant tumors than cells with normal MED1, according to the Rockefeller and ScienceDaily reports.

“This previously unknown transcription-level mechanism helps the cancer cells survive stressful conditions, so targeting it could disrupt a key survival mechanism that some cancers rely on,” Lin said in comments released by Rockefeller University and carried by ScienceDaily.

Roeder added that “this molecular switch is mediated by a generic transcription complex normally required for all protein-coding genes,” and that its subunits can be repurposed for functions that allow cancer cells to survive and grow in high-stress environments, according to the same institutional summary.

Lin described the effect as a regulatory switch: “Our work reveals that the acetylation and deacetylation of MED1 act as a regulatory switch that helps cancer cells reprogram transcription in response to stress, supporting both survival and growth,” he said. He noted that in cancer — particularly ER+ breast cancer — this pathway may be intensified to support abnormal growth and survival and could inform future drug development.

Roeder said the MED1 regulatory pathway appears to fit into a broader paradigm in which acetylation controls transcription factors, pointing to earlier work on the tumor-suppressor protein p53 from his lab. He emphasized that understanding such basic mechanisms can reveal pathways that might eventually be leveraged for new therapies.

Taken together, the findings highlight how fundamental research on transcriptional regulation can uncover therapeutic opportunities, especially for ER+ breast cancers and potentially other malignancies that rely on stress-induced gene reprogramming.